Originally formed in July 1918, 139 Squadron was a fighter squadron towards the end of the First World War but was disbanded in March 1919 and reformed in 1936 as a bomber squadron, initially with Hawker Hinds and Blenheim I’s. 139 Squadron saw continuous service in one theatre or another throughout the war, and carried out the most bombing raids of any squadron in No. 2 Group.

“We Destroy at Will”

139 Squadron entered World War 2 equipped with the Blenheim and holds the honour of flying the first RAF sortie of the war, from Wyton in Huntingdonshire, across into German airspace just as Neville Chamberlain was broadcasting to the nation. It was an armed reconnaissance mission into German airspace, made on 3rd September 1939 and was already on its way as Chamberlain stood up to make his speech. The purpose of the mission was to take photographs of the German Fleet at Heligoland Bight (Schilling Roads) near Wilhelmshaven. The aircraft was flown by Flying Officer A Macpherson in a Blenheim (N6215) Mk IV.

The following day, the first defensive sortie of the war was mounted by 15 Blenheim’s of 2 Group Bomber Command, of these, 5 failed to locate the target, German shipping in Schilling Roads, due to poor weather and of the 10 that found the target, 5 were shot down by anti-aircraft fire. The bombs did little damage to the target and this proved quite typical of the bravely executed but largely ineffective and very costly Blenheim bombing raids that were to follow. In this action, Sergeant George Booth, an observer with No.107 Squadron became the first British Prisoner of World War 2 when his Bristol Blenheim was shot down over the German coast on 4th September 1939.

After Norway and Denmark were occupied, the main assault against France began in earnest on 10th May 1940 and the AASF (Advanced Air Striking Force) under the command of BAFF (British Air Forces in France) found themselves up against an much larger adversary with 1,486 bombers and 1,264 fighter aircraft. AASF had at the time 8 Squadrons of Fairey Battles, 2 Squadrons of Blenheim bombers (including 139 Squadron) and 2 Squadrons of Hurricanes, which was quickly increased to 6 Squadrons at the request of BAFF in response to the German advance.

The Bristol Blenheim was the front line light bomber right from the beginning of the war and at this time, 139 Squadron was a day bomber squadron equipped with Blenheim Mark I’s, when it took its aircraft to France in December 1939.

139 squadron distinguished itself during the German advance into France when on May 12th 1940, nine Blenheim’s of 139 Squadron made a desperate attack on the Maastricht bridges in Belgium in an attempt to halt the German advance, resulting in 7 out of the 9 aircraft being shot down and the squadron was quickly overrun during these early days of the German advance in May 1940.The Fairey Battles fared no better with 4 out of 5 being destroyed in their first encounter and the 5th crashing on its return to its airfield. 114 Squadron, the other Blenheim Squadron, was destroyed on the ground meaning that within just a few days the AASF was down to 25% strength.

A quick change in tactics resulted from the dreadful loses suffered in France and the early days after Dunkirk and the bomber squadrons moved to a policy of night bombing only, changing at that time the loses of one aircraft in ever two sorties to one aircraft in every 200 sorties but the Blenheim squadrons were required to continue flying during the day, thereby continuing the dire loses. To maintain morale with the general public, these losses were not publicised or made known. This continued after Dunkirk and into the Battle of Britain as Bomber Command took the war back to the Germans as the fighter squadrons defended London, and Britain, from the German Luftwaffe.

Having lost most of its aircraft in France, the Squadron was in dire need of reequipping and was the subject of a campaign called ‘The Bombers for Britain Fund’. The Squadron name is derived from the resulting fund-raising campaign in the early years of the war led by the Jamaican newspaper, ‘The Gleaner’, with enough donations via the newspaper and Jamaica itself to buy 12 Blenheim’s by 1941. On the 26th June 1941, 139 Squadron was renamed 139 (Jamaica) Squadron in recognition of the important part Jamaica had played in equipping the squadron.

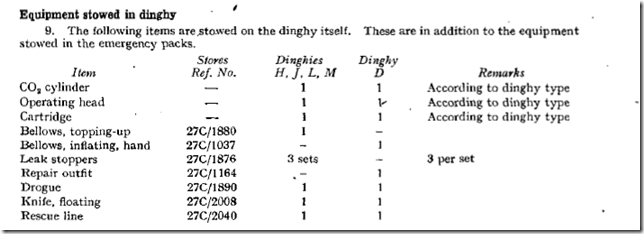

Poster held by the Discovery Museum at Newcastle.

139 Squadron was to suffer a similar fate to their experiences in France in 1942 when in February, equipped with Hudson aircraft, it would reach Burma, just in time to be caught up in the Japanese advance whilst they were based at Akyab and Chittagong. Again, badly mauled, the surviving aircraft and crew would be absorbed into 62 Squadron. The Squadron was reformed, returning to Horsham St. Faith on 8th June 1942 and was initially equipped with Blenheim’s before quickly being re-equipped again, this time with Mosquito’s, becoming a pathfinder force in July 1943.

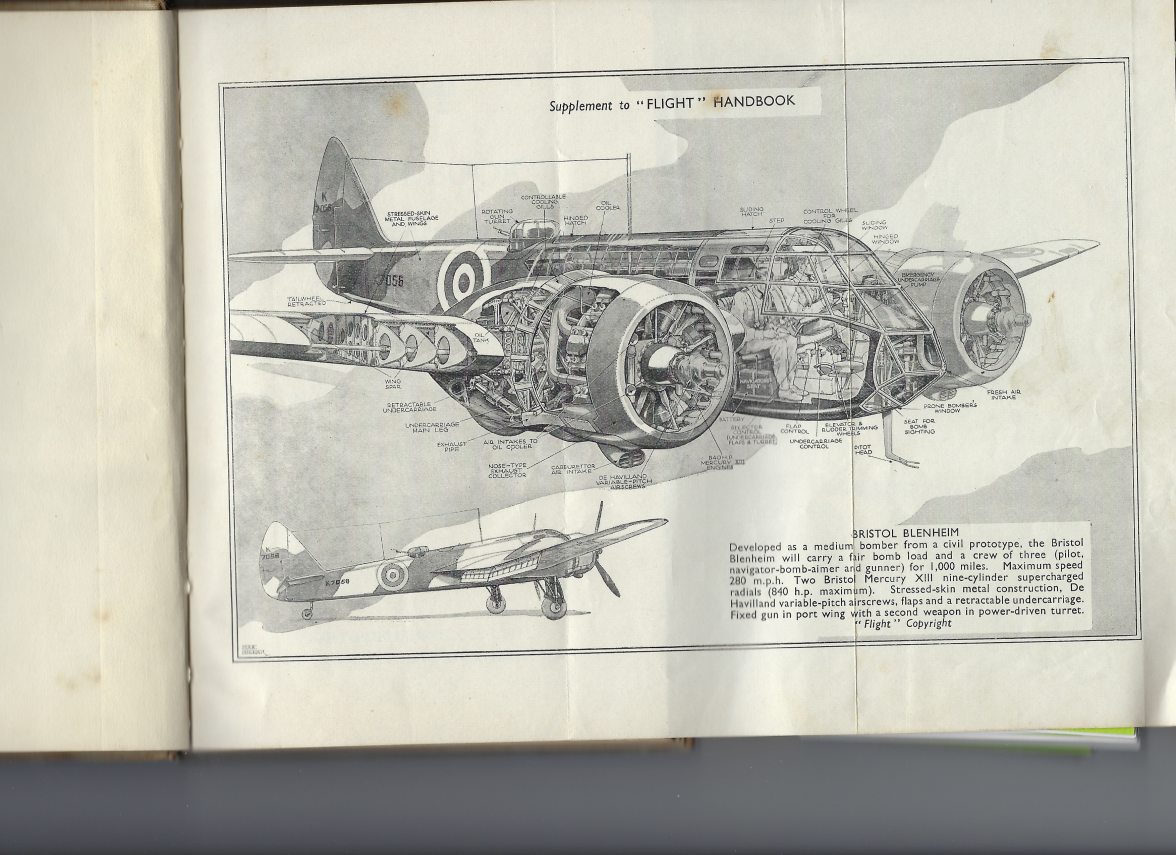

139 Squadron in 1941 was re-equipped with Bristol Blenheim Mark IV’s, developed from a high-speed light passenger aircraft that was initially designed in 1933, capable of carrying up to 8 passengers within an all metal cantilever stressed skin fuselage, which was first displayed at the 1935 Salon Internationale de L’Aeronautique in Paris.

The new design had been put forward originally to be powered by two 500 hp Bristol Aquila I engines, which were then under development. The original design, the Type 135, had an anticipated top speed of 180 mph (290 km/h) but lacked the range to meet current day requirements of its intended customers. Changes were proposed that included reducing the fuselage cross section to reduce drag and replacing the 500 hp Bristol Aquila engines with two 640 hp Bristol Mercury VI radial engines, driving fixed pitch four blade propellers. Design work started on the now designated Bristol Type 142 with Lord Rothermere as its principle source of funding.

Bristol had learned however that the government planned to expand the RAF and with the anticipation of possible future contracts decided to fund a parallel design called the Bristol Type 143 as a private venture. The Type 143 featured a longer nose and longer undercarriage doors.

The type 142 was first flown at Filton on 12 April 1935 and was to spark off a great deal of excitement when during its initial trials it was found to be some 30 mph (48 km/h) faster than the prototype of Britain’s most-recently procured new biplane fighter, the Gloster Gauntlet. The aircraft was named ‘Britain First’, and was presented to the nation by Lord Rothermere after the Air Ministry had requested that they might retain it for a period of testing to evaluate its potential as a light bomber. It was the subject of a number changes and was then moved to Martlesham Heath for RAF trials. It proved so successful that in 1935 the Air Ministry issued Specification B.28/35 for a military version with similar performance. This formed the birth of the Bristol Blenheim which was to prove an important interim weapon at the beginning of World War II.

The “Bristol” Type 142 “Britain First”

Bristol were aware of Air Ministry interest in the Type 142 so they busied themselves in evolving a military version (Type 142M) of this aircraft, and in the summer of 1935 the Air Ministry decided to accept the company’s proposal, placing a first order for 150 aircraft to Specification B.28/35 that September. The new aircraft was very similar to the Type 142, but there had of course been some changes to make it suitable for the military role, including amendments to accommodate a bomb aimer’s position, a bomb bay and a dorsal gun turret.

Following the first flight of the prototype, on 25 June 1936, it was moved to Boscombe Down on 27 October 1936 for the start of official trials, with initial deliveries to RAF squadrons beginning in March 1937. In July 1937, the Air Ministry placed a follow-on order for 434 additional Blenheim Mk Is, as the type had by then been named. Export versions of the Blenheim Mk I were sold before the war to Finland, Turkey and Yugoslavia and were also built under licence by these first two nations. In addition, a small number had been supplied to Romania as a diplomatic bribe in 1939, but this proved to be unsuccessful. The result, of course, was that Blenheim Mk Is fought for and against the Allies.

The Bristol Blenheim aircraft, first saw service in March 1937 and was considered at that time to be an outstanding aircraft when compared to the older biplanes that most of the pilots and crew had just moved over from. It was the first all metal stressed skinned monoplane (single winged) that the RAF had ever ordered, and was ordered in large numbers, with a top speed of 307 mph, some 50 to 60 mph faster than the RAF’s frontline fighters of the time. At this time and at the start of the war the aircrew were very happy to be flying the Blenheim compared to all the ancient bombers that were still in service.

Bristol Blenheim Mark 1.

On the outbreak of World War 2 there were very few Blenheim Mk I’s remaining in service with home-based bomber squadrons, having been superseded by the Blenheim Mk IV, but their usefulness was by no means over and many continued to serve as conversion trainers and as crew trainers in OTU’s.

With so many squadrons operating the type, it was inevitable that Blenheim’s should notch up many wartime ‘firsts’ for the RAF, including the first sortie of the war as described above, however, from the beginning of the war, until it was replaced by Douglas Boston’s and de Havilland Mosquitoes in 1942, Blenheim Mk IVs were used extensively in the European theatre. Although vulnerable to fighter attack, they were frequently used for unescorted daylight operations and undoubtedly the skill of their crews and the aircraft’s ability to absorb a great deal of punishment were the primary reasons for their survival, because high speed and heavy firepower was certainly not their strong points.

Bristol Blenheim Mark IV.

Bristol Blenheim Mark IV.

Last of the direct developments of the Blenheim design was Bristo1’s Type 160, known briefly as the Bisley, which was to enter service in the summer of 1942 as the Blenheim Mk V. Envisaged originally as a low-altitude close-support bomber, it was in fact to be built for deployment as a high-altitude bomber, powered by Mercury XV or XXV engines. Except for a changed nose, some alterations in detail and updated equipment, these aircraft were basically the same as their predecessors. Some 942 were built, all produced by Rootes at their Speke (South Liverpool) and Blythe Bridge (Stoke-on-Trent) factories, and the first unit to receive Blenheim Mk Vs was No.18 Squadron. The type was to equip six squadrons in the Middle East and four in the Far East, where they were used without distinction. This resulted from an increase in gross weight of over 17 per cent which, without the introduction of more powerful engines, had brought about a serious fall of performance. It was only when the Blenheim Mk Vs were deployed in the Italian campaign, contending with the advanced fighters in service with the Luftwaffe, that losses rose to quite unacceptable proportions, and the Blenheim Mk Vs withdrawn from service.

The Bristol type 160 was developed in Canada as the Bolingbroke. Operational use of which, was limited to the Royal Canadian Air Force at their home in Canada and the Aleutian Islands. No 8 (Bomber Reconnaissance) Squadron was the first RCAF unit to convert to the Bolingbroke, followed by one other squadron. Bolingbroke’s were used primarily to fly anti-submarine coastal patrols over both the Atlantic and Pacific.

Two RCAF squadrons were assigned to the combined American-Canadian defence campaign to protect the Aleutian Islands and west coast of Alaska from Japanese attack.

Meanwhile, back in Britain, the Blenheim was also used as a night fighter, the first aircraft in the world to carry radar and the first aircraft to carry out successful interception of the enemy both by day and at night. An invaluable tool to the conclusion of the Battle of Britain at night.

All that said, upon the outbreak of World War 2, Germany had developed its Air Force considerably and whilst the Blenheim was considered an outstanding aircraft in 1936, by 1939, with the imminent danger of war, the development of much more advanced, faster, more manoeuvrable and better armed fighter aircraft was already underway and it was totally outclassed by the German fighter aircraft against which it was to be put up against time and time again and equally, it carried an inadequate bomb load when compared with the German Bomber Squadrons.

The Blenheim IV’s had a maximum speed 266 mph at 11,800 ft or a cruising speed of 198 mph and a ceiling of 27,260 ft on a return flight or 22,000 ft fully loaded. A climb rate of 1,480 ft/min. On the outbreak of war, the Blenheim was already outdated when compared to its main adversaries, the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and 110, which were much faster than the Blenheim at that time. In comparison, early war Bf109E-1 (Bf109E-3 figures follow in brackets) had a performance of 289 mph ( 293 mph ) at sea level, 342 mph (348 mph) at 13,120 feet (14,560 feet), 334 mph (336 mph) at 19,685 feet and Bf109F-2 of 1941 performance was even better at 321 mph at sea level, 358 mph at 9,840 feet, 373 at 19,685 feet. 139 Squadrons adversaries in June/July 1941were generally the Bf109f, well over 100mph faster than their own aircraft. Equally, early war Bf110C-1 were no better adversary with a performance of 295 mph at sea level, 326 mph at 13,120 feet, 336 mph at 19,685 feet.

Defensive Armament in the Blenheim’s comprised a total of three 0.303in machine-guns. The Browning machine-guns were belt fed while the Vickers machine-guns, which were more normal for the time, used 50 round circular ammunition pans, not so different to that operated by the Royal Flying Corps in World War 1. The standard rear firing defence consisted of two 0.303in Vickers “K” trainable machine-guns in a power-operated Bristol B. Mk IIIA dorsal turret, or in a power-operated Bristol B. Mk IV dorsal turret. The turret could be wound up or down to assist take-off and cruising speed, but in the lowered position, its use was very limited in both elevation and rotation. The third gun was either a single fixed forward firing Browning machine-gun in the port wing operated by the pilot or, more rarely and lately, a Vickers “K” machine-gun in a gimbal nose gun mount.

Whichever way you look at it, the defensive capability of the Blenheim upon the outbreak of war was totally inadequate when compared to its main adversaries, the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and 110. Initially the German fighters armament was mixed as it went through various changes and developments. The early Bf 109’s carried the twin MG 17’s in the cowling, synchronised to fire through the propeller, holding their rate of fire down to about 17 rounds per second each to match the propellor. The earlier 7.9mm cartridge was slightly more powerful than the .303’s at that time, although it is difficult to make direct comparisons as the bullet weight and muzzle velocity varied according to loading (and the round was improved early in the war with the even more powerful v-Munition). Magazine capacity in the German fighter’s was enough for a whole minute’s continuous firing (reduced from 1,000 to 500 rounds per gun in later versions with engine-mounted cannon). The Bf 109E-1, which was in service in some numbers at the start of the Battle of Britain, also had two more 7.9mm MG 17’s in the wings with 500 rounds per gun, giving 25 seconds of firing. Some were converted to take wing cannon instead.

When the Bf 109E-3 came out it had two wing-mounted 20mm MG-FF cannon comprising a modified Oerlikon FF made by Ikaria Werke Berlin. It fired 134 gram projectiles at 600 M/s (1,970 ft/s), at a rate of about 9 per second. The 60 round drums which fed the cannon ran out after less than seven seconds (and perhaps less than that, as it appears that only 55 rounds were often loaded, presumably in the interests of reliable feeding). Some E-3’s were modified to E-4 standard and redesignated.

The Bf 109E-4, which entered service in May 1940 and was therefore the latest model used at the time of the BoB, introduced the MG-FFM cannon. This was a version of the MG-FF modified to fire the new, thin-walled high-capacity mine shells (Minengeschoss or M-Geschoss). Although containing far more explosive than the MG-FF’s shells, the M-Geschoss was much lighter at 92 grams. It was fired at a higher velocity of around 700 M/s (2,300 ft/s). Ammunition for the MG-FF and MG-FFM was not interchangeable. It appears that MG-FFs were gradually converted to the MG-FFM’s standard and the two terms used interchangeably thereafter.

From the 109F-series onwards, the likely foe of 139 squadron at that time, guns were no longer carried inside the wings. Instead, the Bf 109F had a 20 mm gun firing through the propeller shaft. The change was disliked by leading fighter pilots such as Adolf Galland and Walter Oesau, but others such as Werner Mölders considered the single nose-mounted gun to compensate well for the loss of the two wing guns. Galland had his Bf 109F-2 field-modified with a 20 mm MG FFM autocannon from the earlier models.

In place of internal wing armament, additional firepower was provided through a pair of 20 mm MG 151/20mm cannons installed in gun pods hung under the wings. The gun pods held 135 to 145 rounds for each gun, however imposed a reduction of overall speed of only 8 km/h (5 mph). Although the additional armament increased the fighter’s potency, it had an adverse effect on the aircrafts handling qualities, reducing its performance in fighter-versus-fighter combat situation and accentuating the tendency of the fighter to swing pendulum-fashion in flight.

The comparison with the Blenheim is therefore obvious, the German fighters with 20mm cannon with an effective range of 1,000 yards compared with the Blenheim’s 0.303 inch calibre machine guns with an overall range of 300 yards at the most was not an even match. This meant that they could bring their guns to bear a few seconds before the Blenheim could respond, being able to turn away before the defending Blenheim’s guns were in range. The effective ‘killing’ capability of the 20mm cannon compared to the 0.303 inch calibre bullets does not need further explanation.

A comparison photo of the ammunition used in the Blenheim compared to the Bf 109-F as encountered by 139 Squadron, with some other rounds: from left to right, the 0.303 British (7.7x56R), 0.5 inch Vickers (12.7×81), 0.50 Browning (12.7×99), 20mm Hispano (20×110), 7.92mm v-Munition (7.92×57), 20mm MG-FFM (20x80RB), 15mm MG 151 (15×96), 20mm MG 151/20 (20×82), 13mm MG 131 (13x64B). The important ones being the first from the left for the Blenheim and the 6th from the left for the Bf 109-F that they encountered. Taken from https://www.quarryhs.co.uk/BoB.htm by Anthony G Williams, which has other excellent information.

On the offensive side, the Blenheim had a range of 1,460 miles with a 1,000 lbs bomb load internally and up to 320 lbs of bombs externally on two underwing racks, which were rarely used as it was at great expense to performance. Typical bomb loads included 4 250 lbs bombs or 2 500 lbs bombs or 3 300 lbs depth charges carried internally, plus, on occasions, 4 80 lbs bombs or 2 160 lbs bombs on underwing racks. This meant a 1000LB bomb load compared to the Do17Z-2 with a 2205 lbs bomb load, the He111P-4 with a 2204 lb load internally plus 2204 lbs externally, leaving the Blenheim to compare with the 1110LB internal capacity of the Ju88A-4, but they could carry a further 2210 or 4420 lbs externally. No real comparison.

The Blenheim was therefore used for three types of raids, 1) Circus’s (used, in conjunction with a fighter escort now on the offensive, where the Blenheim’s were targeting a strategic target but were also used as a lure to encourage the German fighters into the air), 2) hiding in the cloud and quick raids on near coastal targets or 3) shipping sweeps within range of the French or Dutch coast.

Maps and details of Horsham St. Faith.

Photo of 139 (Jamaica) Squadron taken prior to June 1941.

On 25th June 1941, after a very short bedding in period, Sgt. Fenton and his crew took off at 08.45 Hours in Bristol Blenheim ‘F’ V5826, together with 3 other Blenheim’s who following at 30 minute intervals including S/Ldr. Thompson DFC and crew. They carried out practice bombing with 8 No. 11 ½ LB practice bombs and were detailed to drop ‘programme behind markers hut’. Attacks were to be carried out between 10,000 and 12,000 feet on individual runs. All crews were to adhere strictly to times on programme. All aircraft were to keep watch on Station Operational frequency, for emergency recall, typically being required to return to Squadron for an invasion alert or an anticipated attack by enemy aircraft. Sydney Smith and crew together with 3 other crews acted as fighter affiliation, pretending to attack the aircraft as they carried out their bombing runs. It was noted that Sgt. Fenton and crew were over the target at 09.30 Hours and were required to be off target at 10.00 Hours. This was one of two practice runs and one training flight carried out by this crew prior to entering operational service but was not necessarily unusual. Eric Sydney-Smith, a pre-war journalist who wrote under the name of ‘Sydney Smith’, had recently been posted to No 139 (Jamaica) squadron, then at Oulton, Norfolk, after returning from a tour of duty in Malta, where he had earned a DFC for attacks on enemy shipping.

Then again on 26th June, Sgt. Fenton and crew in Blenheim ‘Y’ – R3704 undertook a practice high level bombing run at 6,000 feet or cloud base, which ever was the lower, with 8 No. 11 ½ Lb. Practice bombs over Grimston Warren range. 6 Other crews carried out a formation flying practice. Detail 1, Sgt. Fenton and crew, were to drop programme behind marker’s hut. Again, all crews to keep a watch on Station Operational frequency, for emergency.

Meanwhile, on the 28th June 1941, Sgt. Derrick Nabarro, second pilot on board a 10 Squadron Whitley, was shot down by flak over Kiel on the return journey following a raid on Bremen and ditched in Kiel Bay, although Nabarro states in his Escape and Evasion report that they all bailed out. His crew all survived, with the exception of P/O A K Watson, and were taken prisoner by the German’s. They were picked up by a German coaster and Nabarro, who had been injured by flak prior to ditching, was taken to hospital, where he met up with W W Hall. P/O Alexander Knox Watson, air gunner, excited the aircraft earlier by parachute over the sea. His body was recovered and he is buried in Kiel War Cemetery. The husband of Elizabeth M. Watson, of Glasgow.

Unlike the Fighter Command crews, Bomber Command crews were constantly at the mercy of the weather and mechanical failure, neither of which now seemed to plague Ken Fenton and his crew, a stark comparison to his training days.

Then on 29th June 1941, with visibility at 12 miles and 10/10ths Cloud at 2,000ft, no operations were planned, with both 139 Squadron and 18 Squadron resorting to training. Therefore, 7 aircraft carried out a simulation bombing run, whilst Sgt. Fenton in Q – L9208 and two other crews carried out a ‘Local formation within one hour call of base.’

No.11 Group Operation Order No.30 dated 28th June 1941 instructed and provided details associated with Circus 27, Raid I A J 440, to be carried out on the evening of Monday, 30th June 1941 against target No.Z303, the Power Station at Pont-à-Vendin, 3½ miles North North East of Lens, in the French Department of the Pas-de-Calais.

The raid was to comprise 18 Blenheim Bombers from No. 2 Group Bomber Command, including 8 aircraft from 139 Squadron based at Horsham St. Faith and 10 aircraft from 18 Squadron based at Oulton and was to be supported by 19 Squadrons of Spitfires and Hurricanes, this being 2 Squadrons more than were to be able to intercept the bombers over London on Battle of Britain Day, 15th September 1940. 212 aircraft in total, 59 Hurricanes and 153 spitfires, as a covering fighter escort, whose duties would have been as the following:-

Escort Wing; comprising Nos. 303, 306 308 Squadrons, out of Northolt and 242 Squadron from North Weald airfield.

Target Support Wings; comprising Nos. 54, 603 and 611 Squadrons from Hornchurch and Nos. 74, 92 and 609 Squadrons from Biggin Hill, 74 Squadron being sent there from Gravesend earlier that day.

Diversion and Rear Support Wings; comprising Nos. 1, 258 and 312 Squadrons from Kenley, Nos. 145, 610 and 616 Squadrons out of Tangmere and Nos. 65, 266 and 485 Squadrons from 12 Group Fighter Command, allocated for this operation to airfields in the South, namely West Malling and Wittering. All the other Squadrons formed part of No 11 Group Fighter Command.

Being a Circus, there was to be a great deal of fighter escort, the intention being to draw up the German fighters to enable the fighter squadrons to inflict damage on their number. On this occasion, the fighter escort was to include the Tangmere Wing, led by Wing Commander Douglas Bader with eleven other aircraft, including that of Sgt. James McCairns.

Both James Atterby (Mac) McCairns and Robert Alexander (Butch) Morton of 616 Squadron, together with Norman John (Mushroom) Smith of 611 Squadron were involved in this Circus operation as cover fighters and would soon be joining Ken Fenton and his crew, suffering the same fate.

This part of the story, like the rest, is taken from accounts written at the time so l have used the annotation of ME 109 as it appears in the reports whilst the correct wording should be Bf, for Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, literally Bavarian aircraft factory/workshop, where Willy Messerschmitt was the chief designer. He took over the company, which then became Messerschmitt Ag., but the designs started under the previous “ownership” remained Bf-, until the last of these in the form of the Bf-162 after which, and the changeover to Me started with the Me-163, the rocket fighter known as the Komet. Also of note is that in German accounts, the designation always has the first letter as a capital and the second a small letter, i.e. Me, Bf or He. Contemporary British records did not follow this rule and l have tried to stick to what was written at the time.

Back at Horsham St. Faith on 30th June 1941, with so much planning to be done and weather conditions indicating cloud 10/10ths at 1500ft. and visibility of 4 miles, Sgt. Fenton and crew in L for Leather, V6258, were briefed on their intended operations and the Squadron was instructed to take-off at 17.30 hrs. with 8 machines from 139 Squadron, led by Squadron Leader Thompson, DFC on Circus 27, together with a further 10 aircraft from 18 Squadron out of Oulton. They were instructed to rendezvous, over Clacton, with their Fighter Escort on a bombing raid on Pont-A-Vendin Thermic Power Station.

At 11 Group Fighter Command, they reported, weather fair, slight ground haze, thin cloud above 20,000ft. By day enemy effort followed the customary lack of activity experienced during the past ten days so it was decided to go and look for the enemy, therefore Circus XXVII was to take place. The same day, Hornchurch reported ‘An early morning mist and high cloud soon gave place to another day of blazing sunshine. Defensive patrols of the usual type kept the squadrons fairly busy most of the day and it was not till after tea that we decided to go and look for the enemy. This would form the basis of Circus 27. The sectors role was to supply the target support wing, which flew over 18 bombers while they made what looked to be a very successful attack on a Power Station near Lens – almost our deepest penetration to date’.

Wing/Commander Peter McDermott, DFC, DFM comments on Bomber Operations in 1941, so similar to what Ken would have experienced, except he was sent out in daylight:

There were, to my mind, several distinct yet merging stages in a bomber operation. Preliminaries were the announcement that ops were on that night, followed by the names of the selected crews. Then we NFT’d (night flying test) our aircraft, usually done by the pilot and WOp/AG, although the nav would sometimes come along. On landing, the aircraft would be parked on the edge of the perimeter track (later in the war to be redubbed ‘taxiway’ – a real war – winning contribution!) ready for bombing up. Sometime in the late afternoon or early evening came main briefing in the station briefing room, when the target would be revealed along with timings, and various specialists would have their say. This would cause either hilarity (“piece of cake”), minor depression (“Jeeze – there again!”) or disbelief (“Not with this weather forecast, surely”). There was also at that time a secondary target plus SEMO (self evident, military objective) and MOPA, (military objective previously attacked). Take off time was generous – at least half an hour for the station – and TOT (time on target) even more so. (In my second tour with No 8 Group we were expected to bomb within ten seconds of TOT or else! How quaint the relaxed procedures of 1941 then seemed). Crossing points out over the UK coast and in at the enemy coast were detailed (the former so that coastal convoys could be warned, but this didn’t stop them regularly pasting us) but from there on things were largely discretionary – concentration in space and time was very rudimentary. According to its experience (or lack of it), each crew planned its route so as best to avoid known searchlight and flak concentrations. Height was often a matter of ‘what you could manage’; some Hampdens would struggle fully loaded at anything much over 10,000 feet while others might make 13,000 plus. At this time, we were also issued with our escape and survival pack (silk maps, miniature compass, fishing line and hook, Horlicks tablets, Halazone tablets – for water purifying – and Benzedrine tablets to keep us going if trying to evade capture after being shot down), and ‘flimsies’ (recognition signals and other secret procedures printed on rice paper and to be eaten rather than allowed into enemy hands, I tried it once – they were totally inedible). Better were the flying rations, chewing gum, an apple or orange and a bar of chocolate; I saved the latter and concentrated on the gum, – supplemented by my wife’s efforts – plus caffeine tablets to keep me going during the eight or nine hours’ flight. Then we were free until the operational meal before final briefing at the squadron when the latest winds were applied to the track and recognition cartridges (‘colours of the day’) drawn.

What were our feelings during this time’? No two people were the same, I’d guess, and probably different for each trip. Wild excitement, curiosity even, certainly on trips early in one’s tour. Varying states of anxiety if the weather forecast was lousy – as it often was that winter – ranging from “It’s bound to be scrubbed” to “Well; it bloody well should be scrubbed”. Some psychics became convinced that this one was IT. One such WOp/AG whom I tried to talk out of his utter depression pre-take-off actually blew up outward bound over the UK coast, so maybe there was something in it. Some apprehension might be felt by the experienced who knew that a particular target was likely to be a stinker – in other words, all sorts of mostly private emotions hidden by jocularity and banter. There must have been some fear, but I never saw it evinced. And I knew of only one case of cowardice – not the so called LMF (lack of moral fibre) but sheer planned cowardice – during my eight months’ tour.

Finally, we got into our flying gear and were ferried to our aircraft, dispersed maps and other gear and, after a final pee against the tail wheel to ensure a safe return, climbed in and settled ourselves. Start up, engine runs, chocks away and a final wave from the ground crew (devoted and very hard-working chaps) and taxy to the take-off point. There we would get a green Aldis signal (radio silence ruled), a farewell from the ‘goofers’ who often gathered there, then off — sometimes in the fading evening light but more often into pitch black night. I loved instrument flying from my first training experience, so didn’t mind either way. After all the preparation, we were en route for the Reich!

A climb over base to ‘set course height’ (bloody dangerous on dark nights with so many aircraft milling about) continued to the coast with pinpoints used to check the wind. If weather prevented this, one was left with directional loop bearings, often unreliable. And from take-off until touchdown, each crewmember was on the alert. For me (‘Skip’ or ‘pilot’ for the whole trip) it was sweeping the whole sky and land for signs of friendly or enemy aircraft, flak and searchlights ahead, a constant eye on the blind flying panel and the multiplicity of engine and other instruments and gauges, checking on the rest of the ‘crew from time to time, ordering “Oxygen on” at 10,000 ft and trying to help the nav with pin-points – generally managing the affair. For the navigator (addressed as that or ‘nav’) it was pin pointing, making the best use of any navigational information or aid he could get (drift readings from his bombsight or lower gunner, loop bearings, occasional not very reliable star shots), passing me any changes of course and, between times, keeping an eye out for anything undesirable. The WOp/AG (wireless op on the intercom) kept a wary eye from beam to beam aft, noted and kept me informed of the half hourly Group broadcasts which would incorporate a recall if necessary and, of course, would transmit any signals if I ordered him to break radio silence. Finally, the lower gunner – also, in my case, the reserve wireless operator – kept what lookout he could from his cramped and restricted position in ‘the tin’ and tried to avoid a numb bum! He might also throw out a flame float or gash incendiary to take a drift bearing for the navigator. We all began getting very cold – heating was rudimentary. Flak at the coast and then the searchlight belt were our next worries. This stretched from the north of Holland in a solid swathe through Belgium and into northern France and was always a total pain in the rear end. It was eerie and scary, but had to be negotiated. The over-worried were liable to be wafted miles off track avoiding cones, often preceded by getting caught in a ‘master’ beam on which other lights would converge. The trick, as far as I was concerned, was to watch the approach of the master beam and then turn across it losing, if it could be spared, a little height but always maintaining an average course. When actually coned, more drastic action was called for – a steep dive and alteration of course was often effective. The thing to avoid at all costs was an aerobatic display; the cone just kept on you while it was filled with flak until the inevitable result. We saw it often enough, and the lights would follow the burning wreckage down to the ground. Nasty.

Once in the target area, the actual aiming point had to be located – area bombing wasn’t then policy. Detailed target maps showed hospitals, which had to be avoided at all costs. In 1941, there was no disgrace in bringing one’s bombs back if the aiming point couldn’t be identified. Cologne and Dusseldorf, given reasonable weather, were easy – the bends of the Rhine were a dead give-away in locating the aiming point. But searchlight dazzle, heavy flak, cloud and poor visibility would defeat the most determined efforts in those days before the boffins had given us better methods. The weather in that winter of ‘41/’42 was often most unhelpful; and as opposed to the ordered in-and-out of later days, there was often a lot of traffic milling around the target area searching for the aiming point.

After the bombing run, necessarily holding the aircraft steady come what may, it was away on the long haul back home. If over the sea and well to the north of the Frisian Islands, one was spared the flak and searchlights, give or take the odd flak ship, but one still needed to be wary of night fighters. A return over land meant more problems for hours until one was clear of the enemy coast.

Those hours over the North Sea were some of the happiest ones of my flying life when the weather was kind. The worst part of the trip – one hoped – was over and I could feel really at one with nature. I seemed to be suspended alone in space (and in the Hampden, each crew member was alone from start to finish) and free to meditate on the magic of being there in the immensity of the sky surrounded by millions of stars with the good old Pole Star on my right shoulder. Sometimes I would open the hood, despite the appalling but welcoming roar of the engines (the ‘Peggies or Bristol Pegasus XVIII radials) and feel even more part of the cosmos. Mind you, I would often do this just to try to stay awake, for a long night trip could induce the most appalling fatigue, probably accentuated by lack of oxygen, and I can remember occasionally hallucinating, although we didn’t use that term then.

Eventually, there was the welcoming sight of the UK coast and then the flashing of the airfield beacon. This could all be spoilt by bad weather, problems with a damaged aircraft, fuel shortage or other troubles ruining what should have been a joyful moment! But the concentration of approaching the hooded flares, the feel of the wheels bumping over the grass (no runway at Luffenham), the waving torches guiding us to our dispersal, the profound silence as the engines were stopped, the crackles of cooling exhausts, climbing out to the ground crews ‘Have a good trip, Sarge?” – these were all part of the joy of another trip completed towards the impossible-of-achievement 200 hours operations for a first tour.

Changing out of flying kit, walking to SHQ for debriefing, swapping tales of the trip with other crews, the gradual realisation that someone was missing, the post-flight meal (the egg and bacon reward for going!) and then, whatever the hour, a quick game of snooker before settling down to a profound slumber. Another one under the belt!

That has to be one of the best descriptions regarding bombing operations in the early part of the war, a Hampden, not a Blenheim but equally vulnerable. Guy Gibson, in his book ‘Enemy Coast Ahead’, one held in my father’s personal library, remarked that very early on – 1940 – it was possible to take off at a time best suited to the crew. In those early days there was no concentration points where the bombers would head for and then join in the ‘bomber stream’.

For this operation, the 139 Squadron crews were selected to comprise:-

S/LDR. Thompson DFC, Sgt. Hepworth, Sgt. Turner. (This Crew had just returned from operations in Malta, when they were involved in the loss of Blenheim V5460 (XD-G) of 139 Squadron which took off on 3rd June 1941 from Luqa, Malta at 13.00 hrs. on an anti-shipping patrol and was lost during an attack on an 8,000 tonne vessel, when the aircraft was hit by debris whilst attacking the ship and crashed in the sea, significantly, with this crew surviving to fight another day).

Sgt. King, F/O. Loffatt, Sgt. King

Sgt. Norman Baron DFM, Sgt. Kenneth William Hopkinson, Sgt. Robert Walter Ullmer DFM (20th July 1941, this crew took off at 13.24 hrs. in Z7499 from Oulton, together with 2 other aircraft, on an attack on a 8,000 tonne tanker off Le Touquet, at 50 feet, a terrific explosion was seen to the stern of the vessel, followed by a huge column of black smoke. The aircraft report being attacked by M.E. 109’s but it is reported that Baron’s aircraft was shot down by flak and crashed into the sea off Le Touquet, all crew killed. The bodies were eventually washed ashore. Sgt Baron is buried in Blankenburg Communal Cemetery, Belgium and the graves of his crew are in the Boulogne Eastern Cemetery).

Whilst on secondment to Malta from 139 Squadron, having just returned to Horsham St. Faith on 11th June 1941, both Baron and Ullmer were awarded the DFM on 22nd June 1941, which was gazetted on 8th July 1941, in that, in May, 1941, Sergeant Norman Baron (758054) and Sergeant Robert Walter Ullmer (759266) as pilot and wireless operator air gunner respectively, took part in an attack against a 6,000 ton enemy merchant vessel. Three direct hits were obtained and it was subsequently learned that the ship had been abandoned. A few days later, following a report that drifters were taking off the cargo, they again bombed the ship obtaining hits which caused smoke to be emitted.

Later, in June, 1941, Sergeants Baron and Ullmer participated in an attack on a large and strongly escorted convoy: The particular section attacked consisted of six merchant vessels and six destroyers. Bombs from one of the leading aircraft struck two of the ships one of which was an ammunition ship which blew up with terrific force and the aircraft in which Sergeant Baron and Sergeant Ullmer were flying was severely damaged by the blast. Despite the wrecking of his turret, Sergeant Ullmer secured excellent photographs of the damage caused to the convoy and Sergeant Baron succeeded in flying the damaged aircraft back to base.

Both airmen have consistently displayed great keenness, courage and determination. There was no mention of their Observer.

S/Ldr. Eric Sydney-Smith DFC, Sgt. Ryan, Sgt. Handley (16th July 1941 took off at 16.00 Hrs in K 7632 and shot down on a raid on Rotterdam Docks by flak ship and crash landed in Waalhaven District, all the crew became POW’s, however, by this time Sydney Smith was flying with a different crew. Sgt. Ryan was replaced by PO R A White and Sgt. Hadley had been replaced by F/Sgt. Caban (DFM)

Sgt. Kirk, Sgt. Regis, Sgt. Holmes

PO Roy Stewart Wilson, Sgt. Richard Thomas Stephens, P/O Frank Wilfred Turner (14th July 1941, this crew took off at 06.25 hrs. in R3704 from Oulton and was shot down by fighters off Le Havre, where they were attacking ships in the harbour and the harbour installations themselves. The crew are buried in Ste. Marie Cemetery, Le Havre, Seine-Maritime, France). PO Wilson (64904) RAFVR, died aged 19, the son of James Henry and Eileen Gabrielle Wilson of Ealing. Middlesex). This crew had trained at 13 OTU with Ken and his crew and were posted to 139 Squadron on 19th June 1941, 2 days after Ken.

Sgt. James Archer Cormack RAAF, Sgt. Archibald Murdock Smith, Sgt. James Alexandra Gordon Forsyth (On 3rd July 1941, this crew took off in V6452 at 10.22 hrs. from Horsham St. Faith to bomb a target at Hazebroek and was never heard from again, the reason for the loss has not been established. All buried at St. Omer in the Longuenesse Souvenir Cemetery).

Sgts. Ken Fenton, Alan Fuller and Robert McDonald

From this you will see that of the 8 crews that took part in Circus 27 from 139 Squadron, at the end of the month of July, 3 crews would remain operational with 2 becoming prisoners of war, whilst the remaining three crews were to become casualties. Not a promising future for a fledgling Blenheim crew.

The 10 No. 18 Squadron crews from Oulton comprised:-

W/C Graham, P/O Brown and F/O Sherring.

F/L W Hughes, Sgt. M Wilding and Sgt. J Hunter. (20th July 1941, this crew took off at 15.30 hrs. from Horsham St. Faith and during its attack, the aircraft clipped the mast of the ship that they were attacking and crashed into the sea off Le Touquet. Their bodies were never recovered. All are commemorated on the Runnymede Memorial. F/L W Hughes at this point had been promoted to Acting squadron Leader, indicating the loss rate within these Blenheim Squadrons).

Sgt. Scott, Sgt. Scully and Sgt. Mansard.

S/L Roe, Sgt. Stephenson and Sgt. Jones, R.

Sgt. Jefferson, Sgt. Millns and Sgt. Scotney.

P/O A F H Mills, P/O W A Staniland and Sgt. L C Mitchell. (On 12th August 1941, this crew took off at 09.25 hrs. from Horsham St. Faith and ditched in the North Sea, after clearing the Dutch Coast, homebound. The aircraft was claimed by Oblt. Baron Freiherr Hubertus von Holtey Stab/JG26 – South of Vlissingen at 13:28 (wings to Victory 124). The crew became POW’s. S/L Mills RCAF POW 3706 in camps 10c and SL3, F/O Staniland POW 3736 in camps 10c and SL3 and Sgt. Mitchell POW 147 (or poss. 745) in camps 3E and 357.

S/L Monroe, Sgt. Harbord and P/O Applebee. Frank Harbord Joined the RAF to train as navigator in 1938. By 05/1940 he was part of the Battle of Britain flying from Watton, bombing German invasion barges at low level & often attacked by Me Bf 109s both over the target and on their return. Posted to 13 Operational Training unit in October 1940 for a period of rest he would have come across Ken Fenton and his crew, covered earlier. In May 1941, he was posted to 18 Squadron at Oulton, billeted in Blickling Hall, where he formed up with Monroe and Applebee and took part in this raid. In the late 1990’s Frank wrote his memories of the RAF in ‘Familiar Voices’, published by Able Publishing in 1998, in which more details are recorded, but he does not record his time with 18 Squadron or this specific raid, but records the casualty rate as being very high as the squadron was engaged in low level shipping strikes (altitude of fifty feet or less), interspersed with high level raids (altitude of ten thousand feet) over Northern France known as ‘rhubarbs’ and or ‘circus’s’.

Frank Harbord wrote in his book ‘Familiar Voices’ :-

‘Now on these high level raids twenty-four Blenheim’s would have an escort of over two hundred fighters, a close escort of twenty-four Hurricanes, and Spitfires and Hurricanes stepped up from five thousand to twenty thousand feet.’

‘Life was difficult for the pilots of the ME 109’s. Usually the RAF claimed about twenty German aircraft shot down. Our losses were light, the Blenheim’s usually returned unscathed. The pilots of the ME 109’s had to content themselves with headlong dives through the Blenheim formation. It was a little disconcerting to see a ME 109, painted yellow from the spinner to the wing leading edge, standing on its nose about ten feet in front of your windscreen even although it was gone in a flash.’

In June 1941, Air Vice Marshall DF Stevenson (2 Group Bomber Command) sent 18 Squadron congratulations on raid on large power station in France led by Sq/Ldr SJ Monroe DFC with Sgt Frank Harbord (Obs) & P/O Eric Applebee DFM (Wop/AG).

Sgt. Wood, Sgt. Johnson and Sgt. Allan.

Sgt. Milson, Sgt. Millar and Sgt. Moore.

F/L Tudge, Sgt. Penn and Sgt. William Douglas Barker. (10th July 1941, this crew took off at 10.40 hrs. from Watton in Blenheim V6398 YH-A with 21 Squadron to bomb the Cherbourg Docks and were not heard from again. This operation was the crews first and last with 21Squadron, having recently been transferred over from 139 Squadron, John Tudge had been promoted from F/O to S/L in three weeks due to the losses that had been sustained. Having left Watton and rendezvoused with the fighters at Portland Bill , they proceeded to Cherbourg at very low level, a typical survival trick of the Blenheim crews, where they lifted up to attack a moored ship and the aircraft clipped the mast top, smashing the camera. The Observer was heard to shout as the camera had been wrecked and he thought he had some great photographs. The pilot continued to pull the stick back to get over the harbour wall, the air gunner thinking because of all the shouting that they were on fire, they cleared the harbour wall but were too low to get over the buildings in the harbour area. The pilot, seeing an oil pumping station, dropped his remaining bomb setting it on fire and set off home. The aircraft had been damaged by flak and about 10 miles off the French coast they had no option but to ditch the aircraft and were picked up and became POW’s. The crew became POW’s. S/L H. J. C. (John) Tudge in Camps 7C/L3, POW No.1621, Sgt C. G. Penn reports being captured on 11th July 1941, whilst with 21 Squadron and in Camps 9C/L3/L6/357, POW No.39256 (possibly 39258) with Sgt W. D. Barker, POW No.39292.

Official British Photograph – How the RAF gets it’s pictures. After a flight over German territory. The pilot asks the observer if all went well. The observer replies with “Thumbs up”

Official British Photograph – How the RAF gets it’s pictures. Film exposed over Germany is taken at the double from a Royal Air Force aircraft (Blenheim) to a waiting car.

Following the final clearance and with all aircraft at the ready, 139 Squadron took off at 17.32 hrs from Horsham St. Faith and 18 Squadron at 17.11 hrs from Oulton, the 18 bombers made rendezvous with the Escort Wing over Clacton at 7,000 to 8,000ft at 18.00 hrs. One aircraft of 139 Squadron, piloted by Sgt Kirk quickly notified the tower and abandoned the operation over Martlesham due to excessive over heating of the port engine, not an uncommon fault, and returned to Horsham St. Faith, leaving 17 Blenheim Bombers for the raid.

Escort Wing Close Support was provided by 242 Squadron, North Weald, who took off with their Hurricanes at 17.45 hrs and rendezvoused with bombers and the 3 Squadrons providing the Escort Cover Wing, which comprised three Squadrons of Spitfires, 303, 306 and 308 Squadrons out of Northolt/Martlesham. 303 leaving Northolt at 17.50, 306 at 17.45 and 308 leaving at 18.00.

The Target Support Wing, Spitfire Squadron Nos. 54 (low Cover), 603 (Top Cover) and 611 (Middle cover) left Hornchurch at 17.52 hours, led by 54 Squadron’s 12 Spitfires VA’s including that of Group Captain Broadhurst DSO DFC AFC in a Spitfire VB. On receipt of information that the bombers were 4 minutes late, the wing circled off North Foreland and picked up the bombers 10 miles East of North Foreland at 18.13 hrs at 15/18,000ft to escort them to Gravelines. 603 Squadron had been involved in a Barrow Deep patrol at various times earlier that morning, patrolling off Southend-on-Sea.

The Biggin Hill Wing, comprised Spitfires of Nos. 74, 92 and 609 Squadrons, also made rendezvous with the Bombers and Escort Wings at the same time and crossed the French Coast at 23/28,000ft. 74 Squadron was normally based at Gravesend but was moved to Biggin Hill that morning for this operation.

On arriving at a position 5 miles inland, 603 Squadron (Top Cover) at 18,000ft. were attacked by 3 pairs of ME109’s from 4,000ft., above and behind in line astern and became detached from the wing, the wing braking up and diving to evade. One section dived on a box of 4 ME109’s with another ME109 behind, and destroyed one of them. The Squadron report seeing more enemy aircraft than on previous offensive operations, all in small formations of not more than six aircraft and mostly having height advantage. The Squadron later reported having one pilot missing and heavy Flak being experienced at Gravelines.

54 Squadron also reported that on the way in, North of St Omer, 6 ME109’s dived from West to East across the front of the Wing, travelling very fast as though attempting to make the Wing split up.

Elsewhere, the three Diversion and Rear Support Wings made ready, rendezvoused over Hastings and crossed the French Coast at Le Touquet, proceeding towards St. Omer.

145 Squadron reported a quiet morning with formation flying and weather tests in the morning. Later that afternoon, 12 Spitfire Mk 2B’s took off from Merston at 17.40 hrs. and made rendezvous with the other two squadrons of Spitfires over the base and proceeded to Hastings, where they met the other two Wing forming the Diversion and Rear Support Wing, namely the Kenley Squadrons Hurricanes and the Spitfire Squadrons from 12 Group Fighter Command. Together they then crossed the coast at 20,000ft, passing over the French Coast at Le Touquet at 28,500ft, with 11 aircraft from 145 Squadron.

610 Squadron left Westhampnett with 12 Spitfires MkIIB’s at 17.45 hrs., with 616 and 145 Squadrons. 616 Squadron leading and below, 610 in the middle and 145 above, all in Squadron formation (3 sections, 4 A/C) leaving the coast at Hastings at 20,000ft., making landfall at Le Touquet at 27,000ft. and proceeded towards St. Omer.

616 Squadron, also out of Westhampnett, reported local flying practice in the morning and F/Lt Montgomery doing some air to sea firing. Again, later that afternoon they were to join 610 Squadron, with an additional 12 aircraft including W/Cdr Bader and Sgt. James McCairns, also departing at 17.45 hrs. F/O Casson was promoted to acting F/Lt to take command of ‘A’ Flight.

In support of the Diversion and Rear Support Wings required for the operation, No 12 Group formed a Wing with 65, 266 and 485 Squadrons to act with the other two Wings, as an Offensive Diversionary Patrol and Rear Support Wings, forming 9 Squadrons in 3 Wings in total, a total of a further 98 aircraft.

65 Squadron departed Kirton-in-Lyndsey and 485 Squadron lead by S/Ldr. Knight from Leconfield earlier that day and had already assembled at West Malling, whilst 266 Squadron was already operational from Wittering. 65 Squadron had sent 7 aircraft to West Malling for this operation but one aircraft crashed on landing, this pilot, F/O Lyons, ‘commandeering’ an aircraft from Sgt Nelson and re-joined the sweep, which with one other aircraft being sent to Kirton-in-Lyndsey, left 5 aircraft for the sweep. Reporting the weather to be very warm with some Haze, the aircraft departed West Malling at 17.35 hrs. and Wittering at 17.55 hrs. and as a Wing swept over Northern France in the Le Touquet – St. Omer – Boulogne – Gravelines area at 15/18,000ft.

266 Squadron was to give high cover to 65 Squadron and to patrol St. Omer-Hardelot-Gravelines and they reported that the Patrol was successfully carried out.

The Kenley Wing, Nos.1, 258 and 312 Squadrons, left Kenley at 17.40 hrs. and having joined the other two Wings patrolled aerodromes and landing grounds in the St. Omer – Guines – St. Inglevert – Marquise area at 4/6,000ft.

The main Bomber Force and fighter escort made progress, crossing into France and from this point and during the operation, 242 Squadron, as Escort Wing Close Support reported that they saw no enemy aircraft but that heavy Flak was experienced at Gravelines, during which 1 hurricane was slightly damaged by shrapnel. They also reported that there was no lane of fire as experienced previously between Hardelot and Lille.

Flight of Blenheim’s.

The rest of the escort, 54 Squadron flying at 15,000ft with 611 Squadron above, flew on with the bombers to Merville, having lost contact with 603 Squadron. The additional Target Support, in the form of the Biggin Hill Wing, Squadrons 74, 92 and 609 (Top Cover) moved to 20,000ft., to support the Group.

Prior to Merville and just North of St. Omer, 6 ME109’s dived from West to East across the front of the Hornchurch Wing, travelling very fast but as this was thought to be an attempt to split the Wing, G/C Broadhurst refused to allow 611 to attack.

Arriving at Merville, the Hornchurch Wing circled once over the Blenheim Bombers, and then flew ahead to arrive over the target at 18.36 hrs, 2 minutes ahead of the bombers. The Wing then split into sections of 4 aircraft, remaining in contact with each other and the bombers and continued to circle the target for 10 minutes and watched the bombers successfully bomb the target, Heavy Flak being experienced over the target area. 242 Squadron reported concentrated fire from a four gun battery in the target area and previously from a six gun battery, situated in the sand dunes near Dunkirk.

As the Bombers pressed home their attack, heavy flak was also reported by Sgt. Hepworth of 139 Squadron over the target area but direct hits were still obtained by 11 aircraft on the Power Station, Turbine House and Engineering Works by 4 aircraft of 18 Squadron and the 7 aircraft (one had turned back) from 139 Squadron including Sgt. Fenton’s aircraft. The roof of the Turbine House was seen to collapse, causing clouds of red dust and smoke to rise up, white smoke was also seen on the East side of the Power House after the bombing and flames and dense clouds of smoke covered the area. 18 Squadron confirmed that the 4 aircraft piloted by Monroe, Wood, Milson and Tudge of this Squadron located and successfully bombed the target. Bursts followed by flames and considerable smoke from the Engineering works adjacent to and West of the Power Station and on the Turbine House itself. Dense smoke covered whole target area – and photographs confirmed accuracy of attack, although 18 Squadron thought that only 2 aircraft from 139 Squadron successfully bombed the target. Sgt. Fenton and crew took off with 4 No. 250 lb general purpose bombs with no time delay and 4 No. 40 lb bombs on the flare racks.

Blenheim IV’s

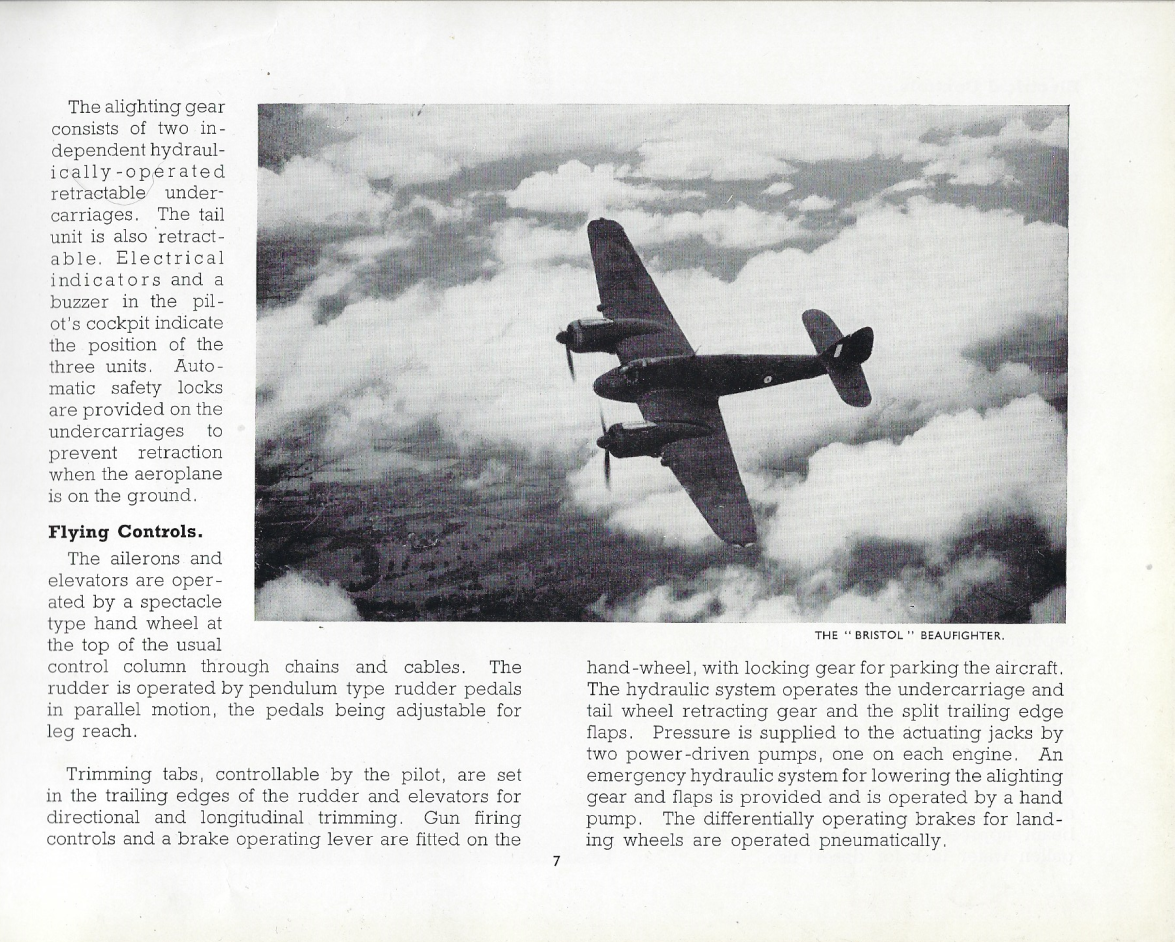

The Bristol Blenheim Mark IV high speed fighter-bomber is an all stressed skin midwing cantilevered monoplane. It has two Bristol Mercury supercharged engines and variable pitch airscrews. The aircraft has a range of 1900 miles at 15,000 feet. The initial climb is 1,500 feet per minute and its service ceiling is 27,000 feet. A Flight of Bristol Blenheims.

The other 6 aircraft of 18 Squadron were unable to locate the primary target until after they had bombed a large factory with two chimneys at Haisnes, 3½ miles North West of primary target at 5030N 0248E from 6,800ft, with 24/250lb G.P. N.D.T. and 23/40lb, scoring 2 direct hits on the North East edge of this factory, other bombers undershot and much white smoke resulted, coming from the area of the factory. It was reported that 1 40lb bomb remained in the racks, hung up and photographs showed however that most bombs fell in surrounding fields. Later, it was shown that the factory bombed proved to be at La Bassée and was mistaken for Z303.

Vertical aerial photograph taken during a ‘Circus’ operation by No. 2 Group aircraft, showing smoke rising from direct hits on the generating plant of the power station at Pont-a-Vendin, France, during an attack by 18 Bristol Blenheim Mark IVs drawn from Nos. 18 and 139 Squadrons RAF.

T G (Jeff) Jefferson recorded, in the excellent blog https://wingcotomjefferson.wordpress.com/:

‘The 1st trip I did was a Circus (27) 30th June 1941 (17.40-19.20) – Target, the Power Plant at Pont à Vendin 10Km ENE of Lens in Northern France, Pas de Calais. Although this was alarming, it’s nothing like a Shipping Beat. You know these Circuses – we used to go over to France at about 12/13, or 14,000ft. We would Bomb a Power Station or something. That would bring all their Fighters up. We had some Fighters staying up a bit later. We wanted to get their Fighters up, for ours to shoot some of them down, and that’s what it was all about. We were really decoys! You sit there, Flying along, and there would be all these black puffs coming! Well, we’d never seen black puffs! Sometimes, when they were near, there was a great Rattling on the Aircraft, and they would bang you up & down. We were issued with ordinary round Tin Hats, which Soldiers had and which we were supposed to put on our Heads – over our Helmets, for shrapnel coming through, you see. Of course, everyone put them under their Seats! Every time we got back if somebody Crashed, all Pilots tore over to the Crash, to see who could get there 1st. Providing the Crew could all be got out, there was all this Fighting! The only piece of Armour Plating any good at all in the Blenheim was behind the Pilot’s Seat. A good old thick piece of steel. If you could unbolt that, and get it out, you would take it down to Station Workshops, get it cut to the right shape, and have it fitted – under your feet – which meant, of course, you had to ‘swing‘ the Compass.’ https://wingcotomjefferson.wordpress.com/

‘At Oulton, we did one or 2 Circuses, which were good, and then we did these Shipping Beats, which weren’t good! I remember, we’d go down to the Flight Office in the morning, and if there wasn’t something we were told to do, we would sit outside on the grass, and watch the Bomb Trolleys go out. If the Bombs were semi-armour-piercing, you’d say, ‘ah, Jeez, and your stomach would sink! Shipping Beat off the Frisians! In fact, this was precisely Tom’s 1st Shipping Sweep – off the Frisians, on 5th July 1941, recording an attack on 10 ‘R’ boats with Machine Gun Fire. If they were 250-pound anti-Personnel Bombs, or General Purpose Bombs, well, it was a Circus, and everyone was as pleased as could be.’

‘A sedate formation transit height over the East Anglian Countryside. Tom Jefferson’s trusty steed, V6519 (WV-X), from his arrival on 18 Sqdn (28th June 1941) until 14th July 1941, encompassing 4 Shipping Beats, a ‘Circus’ Operation and the Attack on Le Havre Docks (10th July 1941). He reluctantly had to change his Blenheim for the Rotterdam Raid of 16th July 1941.’

Following the raid, the Escort then returned to Gravelines with the Bombers. 54 Squadron confirmed they returned to Gravelines in the wake of the Bombers, gradually loosing height and passing over St. Omer at 8,000ft., with the bombers, and arrived at Gravelines at 18.55 hrs.

On route to Gravelines and when passing over St. Omer at 8,000ft, 4 ME109F’s in pairs abreast, aircraft in line astern, dived past 54 Squadron, flying very fast in the opposite direction. G/C Broadhurst once again refused to allow the Squadron to follow, as he considered that this manoeuvre was designed by the enemy to attract our fighters back into France.

A more detailed account of No. 242 Squadron particularly noted that no enemy aircraft were on the ground at the aerodrome at Lille or Béthune.

No 303 Squadron (Polish Squadron) reported ‘another circus, but this time, nothing special to report, except that the ME109’s were weaving!’ Their more detailed report stated that on the way back 4 -7 ME109’s were seen weaving 1,000ft above them but owing to the slow speed of the Squadron they were unable to pull their noses up and attack. One pilot fired at one of these which made an individual attack but no results were observed and the enemy aircraft zoomed away.

I will not go into the heroics of the Polish and other Eastern European squadrons, i hope their stories have already been told, but suffice to say they made a major contribution to World War 2, especially the Battle of Britain. Someone said to me a little while ago, prior to 2016, what had the Eastern Europeans every done for us? Well, quite a lot actually. Many would join my father as POW’s in the coming years and I believe they were protected and looked after by their fellow RAF aircrew, I hope so.

No 306 Squadron report that two pilots had combat with 2 or 4 ME109’s which tried to attack the bombers near the French coast on the way back. One pilot could not observe results owing to looking up sun, but the other saw his bullets strike the cockpit of the enemy aircraft and claims it damaged, It was later confirmed that P/O Langhamer damaged 1 ME109, which he attacked on the return journey.

No 308 Squadron only saw 4 ME109’s well above them near the French coast on the way back.

54 Squadron arrived at Gravelines at 18.55 hrs., where 2 ME109’s were seen cruising up and down the coast at 2,000ft. A similar pair had been seen on previous sweeps, and may either be a patrol to pick up isolated aircraft returning low, or a decoy. On this occasion the later may have been the case for as Red Section was about to attack them, 9 ME109e’s appeared about 1,000ft above. The Squadron manoeuvring to attack, one of them did, in fact, dive towards Red Section, but passed underneath, followed by Blue 1, F/O Charles. F/O Charles made after one that came too close and shot it down. He delivered his first attack from below, firing a 3 second burst at 200yds range, full deflection, then he drew up into an astern position, and delivered a second astern attack as the enemy aircraft banked in a turn. The enemy aircraft then went in a steep dive, followed by Blue 1, who fired a further 3 second burst, at a range of 150yds to 80 yds. Strikes were seen in all these attacks, Blue 1 who was travelling at 400m.p.h. I.A.S. (Indicated Air Speed) pulled out with difficulty at 5,000ft. The enemy aircraft was last seen diving straight towards the ground and is claimed as probable. 2232 rounds were fired. One stoppage in P.2. owing to a weak charge. Standard reflector sight was set at 40ft. 250yds, cine film exposed.

The remainder of 54 Squadron seeing the 8 enemy aircraft preparing to attack, turned towards them whereupon the enemy employed their usual tactics on these occasions and flew back to France.

As noted earlier, 603 Squadron were attacked before reaching their objective. F/O Harry Prowse destroyed 1 ME109E. Sgt. Pilot L. E. S. Salt did not return from this operation and is reported missing. He was last seen over the coast North of Gravelines. 12 aircraft were due for this operation but one aircraft failed to take off.

611 Squadron records ‘Guns were fixed although Heinie was seen in the distance’. Very accurate FLAK was experienced and F/O Williams came back with a punctured tyre. It is believed the bombing of the power station was very effective. S/Ldr Thomas flew with the Squadron for the first time. 12 aircraft were involved.

The diversion staged in the Le Touquet – St. Omer area by nine squadrons appears to have fulfilled its purpose in drawing off opposition, but in spite of this more enemy aircraft than usual were seen by the Hornchurch Squadrons. However, very few actual encounters resulted, and the total score was one ME109 destroyed by F/O Prowse (603) and one probably destroyed by F/O Charles (54) for the loss of Sgt. Salt (Lionel Eric Sydney Salt, 603 Squadron, aged 20, Service No 902909) who is missing in Spitfire R7270 XT-?. Sgt Salt was later confirmed as dead and is buried in Pihen-lès-Guînes Communal Cemetery, Calais. The Wing was rested in the evening and activity was confined to a base patrol and a dusk patrol by 601 Squadron

On the return journey at St Omer 4 ME109’s, in pairs, line astern, at 8,000ft dived past No 54 Squadron of the Target Support Wing. As this was thought to be an attempt to induce our aircraft to turn back into France no attack was made by the Squadrons. Over Gravelines at 18.55hrs 2 ME109’s were seen cruising in line astern along the coast at 2,000ft. No 54 Squadron were about to attack when 9 ME109’s were seen above and to Port, one of these which dived towards a section was attacked and damaged while the others turned away into France, when the Squadron moved to attack. Red marker Flak, accurate for height was seen off Gravelines. It is thought that this flak could have been giving the German Fighters some indication as to where the British aircraft could be found.

The Biggin Hill Wing, reported that although many small formations of ME109’s (mostly E’s) were seen from St. Omer onwards and also on the return journey, 74 and 92 Squadrons saw nothing near enough to engage.

609 Squadron however reported ‘that the last day of the month saw a full 12 aircraft (At Last) take off, experience no cannon stoppages, and shoot down 3 ME109’ with a probable and a damaged in addition. Perhaps 40 enemy aircraft in small formations of ME109’s, mostly E’s, menaced them from target area onwards, many of them in position above our aircraft suggesting that they had received warning of our approach. They were reported as having used ‘nibbling’ tactics, menacing rather than attacking our aircraft. One formation of about 10 remained up in the sun without attacking at all and whenever they did, our aircraft used their superior manoeuvrability to assume an attacking position themselves and individual combats, of which the following is a summary, went in our favour.’

‘Red 1 (S/Ldr Robinson DFC) attacked 2 from below which came over to attack 74 Squadron ahead, chasing them down to 5,000 feet over Merville aerodrome, got behind five which were stalking Blue Section from above and behind, and caused E/A to make-off, but not before he had fired at the last one and caused it to exude glycol and brown smoke. It was probably the same lot with which Blue 4 (Sgt. Hughe-Rees) became involved, and one of which he managed to shoot down from below during a vertical climb, in which encounter after evading an attack by 2 of them, one of which broke upward, the other down, he was again attacked by one. He made steep climbing turn and E/A overtook him, whereupon he went into a vertical climb and fired from astern and below. E/A took no evasive action and emitting black smoke from engine, dived gradually down and crashed.’

‘Over the Foret de Nieppe the squadron was following Wing Commander Malan down to investigate some enemy aircraft below, when Yellow Section saw 4 ME109E’s on their port quarter, quartering to get line astern., Yellow Section pulled up and Yellow 1 and Yellow 2 each selected a victim. Yellow 2 (P/O Ortmans – Belgian) followed his, firing as it climbed and dived and skidded away, with quarter, astern and deflection attacks After the last attack, pieces came off the fuselage and enemy aircraft. Yellow 1 (F/Lt Richey DFC) got astern of his, firing a number of bursts as it made violent left and right turns. He saw flames on port side of engine, which caused it to flatten out, slow down and go down in a spiral, covered with oil and flaming from its engine. Yellow 3 (P/O Malengreau – Belgian) followed it in a steep dive down to 9,000 feet, as it tried to flatten out again, also firing and finally losing sight of it as its dive exceeded the vertical.’

‘Meanwhile ‘F/Lt Richey, formed up with some other Spitfires, at 16,000 feet, saw 6 ME109E’s diving in formation from above and behind. He had an ineffective engagement with one of them, then, finding himself alone again, he dived for a patch of cloud at 800 feet near Foret de Clairmarais. At ground level he saw 2 ME109E’s diving on his tail with a third opening fire from his starboard quarter. A violent climbing turn and side-loop brought him on the latter’s tail, and after two lengthish bursts enemy aircraft dived at full speed from 1,000 feet. After eluding the other 2, also accurate light Flak from St. Omer, F/l Richey flew home, at times below tree-top level, taking a look at France. He reports no cars on the roads, no cows or sheep in the fields, but only horses and horse-carts.’

The Tangmere Wing in their role as Diversionary and Rear Support Wing report that in the St. Omer area 616 Squadron at 24,000ft broke up into “Pairs” and “Fours” as there were 12/14 enemy aircraft in the vicinity. Only one pilot fired but no claim is made. One of our pilots was attacked from behind and below. Sgt McCairns was shot at, explosive bullets entering his cockpit, but he managed to return and land safely and uninjured at base.

610 Squadron made landfall at Le Touquet at 27,000ft. when 50 plus enemy aircraft were reported as having left ground to the East of them. The Squadrons orbited and saw the enemy aircraft a long way below them at a point about 20 miles East of Le Touquet, flying East in pairs in loose formation and numbering about 16 to 20 ME109’s. Several odd pairs of enemy aircraft below them made no attempt to climb up and engage, keeping well out of range. The St. Omer area was covered for about 30 minutes, prior to going out over Gravelines. Small amount of Flak was encountered slightly below and behind at 22,000ft. Enemy aircraft were seen well below when leaving the French Coast and 2 enemy aircraft at the same height as the Squadron in mid-channel dived away towards France before they could be attacked. Landfall made at Dover. Weather Good. 3/10ths cloud at 5,000ft.

145 Squadron crossed the coast at Le Touquet at 28,500ft, with 11 aircraft, where six ME109’s were seen coming up from behind at the same height. The Squadron turned to attack and Blue section (F/Lt Arthur and F/O St. Pierre) engaged the enemy. There was a melee and both pilots fired short bursts from 250 yards. F/Lt Arthur firing a 2/3 second burst with machine guns and cannon, then closing in to about 100 yards from which range a further 1 second burst was fired. F/O St. Pierre was slightly behind his leader and fired a 2 second burst and two 1 second bursts, the last burst being at a second ME109 astern of the victim. Both pilots claimed hits on the ME109, which did a slow role on its back and went spinning down. This aircraft was completely out of control but was not actually seen to crash as the pilots were taking evasive action. These two pilots sharing in the destruction of one ME109. Sgt Robillard (Canadian) came down to sea level and machined gunned a flak gun position about ½ a mile inland from Boulogne, not Le Touquet as previously stated and witnessed his bullets hit the gun. Several members of the gun crew were seen to fall. F/O Forde fired at a ME109 without observing any results. The Squadron then split up and patrolled Pas de Calais area without further incident, prior to returning individually to base at 20.00hrs.

Squadrons 65, 266 and 485 of 12 Group, having carried out their main patrol recrossed the French Coast North of Boulogne, where extremely accurate flak was experienced. 6 ME109’s were seen, 3 to 4,000ft over them but they did not attack. Half way across the channel two pairs of ME109’s were seen flying in an Easterly direction. These enemy aircraft turned South towards France and a pilot of No 65 Squadron attacked and damaged the rearmost aircraft. P/O Mitchell of 65 Squadron claimed 1 ME109 as damaged.

65 Squadron did not succeed in making contact with the enemy before this engagement by P/O/Sgt Mitchell but the squadron also had no casualties and returned safely to West Malling. Nothing of interest was observed during this operation except that severe anti-aircraft fire was met with over the French Coast. One Spitfire of 65 Squadron was slightly damaged by flak but landed safely.

266 Squadron gave high cover as part of the Wing and to patrol St. Omer-Hardelot-Gravelines area and reported that the Patrol was successfully carried out with no enemy aircraft near enough to engage, only enemy aircraft seen in the distance, too far away to intercept before returning to Wittering.

485 Squadron reported that Sgt Thomas was shot at but landed safely at Hawkinge, the aircraft being Cat. AC, but was repaired by the next day.

The Kenley Wing, having patrolled aerodromes and landing grounds in the area of St. Omer – Guînes – St. Inglevert – Marquise at 4/6,000ft and recrossed the French Coast at Ambleteuse and carried out a patrol over the East Godwins in formation of “Fours” at 4/7,000ft until the Bombers and Escort had safely passed over the English Coast. All three Squadrons report very little enemy activity.

71 Squadron, out of Martlesham Heath/North Weald, was not involved in the Circus operation but carried out a Barrow Deep Patrol that day, off the coast of Southend-on-Sea.

139 Squadron, including Ken Fenton and crew returned to Horsham St. Faith at 19.37 hrs., with all aircraft having carried out the bombing raid from 7,500 ft with a total of 20/250lb G.F. N.D.T. and 20/40lb bombs dropped.

242 Squadron, the Escort Wing Close Support, having safely escorted the bombers back without further incident, returned to North Weald at 19.30 hrs.

Close Escort or Escort Cover Wing, including 303, 306 and 308 Squadrons out of Northolt, returned between 19.35 and 19.55 hrs.

Target Support Wing of 54, 603 and 611 Squadrons returned to Hornchurch between 19.20 and 19.30 hrs, with the odd aircraft returning earlier at 18.45 hrs whilst the other Target Support Wing of 74, 92 and 609 Squadrons returned to Biggin Hill between 19.10 and 19.30 hrs. 54 Squadron recorded ‘The end of a successful and adventurous month.’ The following day F/O Prowse of 603 Squadron proceeded on 7 days sick leave. 609 Squadron reported one of their A/C was slightly hit by Flak over Dunkirk and many of the flight landed at Hawkinge, Maidstone and Manston, through shortage of fuel, returning to Biggin Hill later that evening.

Of the Diversion and Rear Support Wings 1, 258 and 312 Squadrons returned between 19.25 and 20.00 hrs, with some aircraft needing to refuel elsewhere, whilst 12 Group, Squadrons 65, 266 and 485 returned between 19.30 and 19.40 hrs. 145, 610 and 616 Squadrons returned between 19.23 and 20.16, again some having refuelled at other bases.

A summary of the operation and conclusion was included in the Circus report.

Summary of Operations.

Enemy – 6 ME109’s destroyed, 2 ME109’s probably destroyed and 3 ME109’s damaged

Own: Bombers – Nil and Fighters – 1 Pilot missing

Conclusion:-

1). A very successful operation in which the bombers appear to have hit the target with great accuracy, and all returned safely to their base. In addition, our fighters destroyed 6 enemy fighters and damaged a number of others in spite of the fact that height advantage invariably rested with the enemy.

2). The impression formed in the last few Circus operations that the enemy fighters are disinclined to press home their attacks on the Bombers and their immediate escorting fighters was confirmed in this operation.

3). At the moment German fighters appear to be studiously avoiding any major engagement with our fighter forces, but on the other hand they appear anxious to draw-off small numbers of our fighters in pursuit of “decoys” with the object of pouncing upon them in superior numbers, or, by shadowing tactics and maintaining a height advantage, they hope by tip and run attacks to pick-off stragglers should such targets be presented to them.

Only a few days later, on 6th July, 1941 11 Spitfires of No 616 Squadron were again part of Target Support Wing B for Circus 35, a raid of some Stirling bombers to Lille, France from 13.30-15.20 hrs.

It was on this occasion that Sgt McCairns would become a POW when his Spitfire P8500 crash landed on the beach near Dunkirk.

An Air Situation Report however gave a slightly different perspective:-

‘Aircraft of Bomber Command continued their offensive operations against targets in North-East France and Germany, in the course of which hits were registered on Steel Works at Lille, Power Stations, at Comines and Pont-a- Vendin nearby, a crowded railway yard near Oldenburg, runways and buildings at Merville Aerodrome and the seaplane base at Borkum.’

A daylight raid on Comines power station in north east France by Blenheim bombers on 28th June scored a direct hit on the turbine hall and caused much damage. Six workers were killed.’