This is the story of a 19-year-old Yorkshire man, my father, who enlisted in the RAF. He was a typical student who had recently left Drax Grammar School (known as Read School, Drax) in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the son of a woodwork teacher who later, near retirement, became the caretaker at the same school as his younger sons to pay for their education. A son who aspired to be an accountant starting with BOCM (British Oil and Cake Mills) in Selby, Yorkshire as a trainee but then, with the outbreak of war, he enlisted in the RAF.

Ken’s mother and father, Percy and Annie Fenton, taken in 1954, “after “mothers operation”, sorry, that is the caption.

Was Ken looking for adventure, or with the outbreak of war, did he just want to avoid the dreadful trench warfare that he would have heard so much about from the previous generation. The majority of family members were in reserved occupation during World War One so did not seem to suffer the loss of life of some families, but this is further research, and there is no doubt they came into contact with others that did and heard their tales.

Ken Fenton was born on 18th July 1920, in Drax, Yorkshire, one of 11 children, the seventh son of the seventh son, born to Percy and Annie Fenton, predominately raised by his older sisters as was normal at that time.

Ken, as a young man, playing football as a goalkeeper together with his brother Tom Fenton, back row, far right.

Picture of Drax High Street taken from the church spire, looking down towards where Ken was brought up.

It is a story within a story, encompassing many others people’s lives and endeavours and covers the events of many of the big campaigns of World War 2. Ken came in contact with many of those involved in these events throughout his RAF career and became part of the much bigger story, the History of World War Two.

He flew with those who were involved in the Battle of Britain, became a prisoner of war, incarcerated with the unlucky ones, or maybe the lucky ones, who were captured at Dunkirk, and he witnessed first-hand some of their horrific wounds. He greeted into captivity at Stalag 357, Fallingbostal, those who evaded death but were captured, during the abortive Arnhem campaign to secure a bridge across the River Rhine, intended to end the war by Christmas 1944.

Scenes of the evacuation of Dunkirk.

He also welcomed and helped acclimatise into the camps, the bomber crews who took part in the greatest bombing campaign the world has ever witnessed. The members of Bomber Command, these everyday people who did as they were asked without a word of complaint, with the odds stacked against them, who up until now have not been recognised for their achievements, barely written about, and only now being considered for the merit they deserve. Those described here are a few of the 125,000 personnel who served in bomber command, over 57,000 of whom perished, which together with the near 11,000 who became POWs as part of Bomber Commands campaign during the Second World War, lead to an estimated 65% casualty rate, the highest of any service of the British Forces during the Second world War.

The RAF Bomber Command memorial in Green Park, a ‘picture’ of a returning aircrew, waiting for the return of the other crews, who with down turned heads have endured so much, sergeants and officers, unveiled on 28th June 2012, 67 years after the war ended.

The bomber crews were proclaimed during the war for their achievements, to great accolade through the propaganda machines and described as ‘the means to victory’ by the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, until after the Germans surrender, when the true extent of the destruction, carnage and death toll was revealed, when to a man, the politicians, including Winston Churchill, decided to distance themselves from this brave and resilient bunch of men. How they must have felt. In fact, it was not until February 2013 that a decision was made to award Bomber Command aircrew with the Bomber Command clasp, not a medal, in recognition for their services but even then, this did not include Bomber Command veterans in other theatres of operation such as Italy, the Middle or Far East, etc., just those involved with operations in Western Europe. Up until then, their only recognition was the award of the 1939-1945 Star.

Many official and commercial books told of the heroic deeds of Bomber Command at the time, encouraging aircrew to join up and help with the bombing war against Germany.

Ken and his crew, together with his fellow pilot cadets, were told during training to expect to survive 6 missions but this did not deter them one bit, even though many of them would not come home, an extraordinary story but not untypical of its time. During their training, they were frequently asked about their next of kin and Religion on form after form, preparing for what may lie ahead. They regularly witnessed death first hand right from the start, a staggering near 8,000 officers and aircrew were to be killed in training accidents during the war. When talking to many vets., when the conversation eventually got round to the casualties, the deaths, they said that at the time anyone who did not come back was just considered to have got an earlier train and that they were all going towards the same destination, it was just, which ‘train’ they were going to catch.

On completion of a tour of duty, normally 30 significant operations (Gardening sorties or Nickelling raids – mining and leaflet dropping, etc. did not count but this was potentially just as dangerous so these operations were unpopular with the aircrews) an aircrew would be rested, which would normally mean a stint in Training Command, giving new recruits the benefit of their knowledge and experience. What was very noticeable to anyone going through their training or indeed, serving personnel, was the lack of bomber crews involved, more personnel coming from Coastal and Fighter Command. The bomber crews rarely survived their full tour of operations to be considered as instructors.

During the time he served with the RAF, as a POW Ken would have met with George Grimson, one of the most prolific escapees of World War 2, who not only escaped many times himself, but unselfishly returned too often to pass on information to the escape committee and who also organised an escape route to help other potential escapees to evade the Germans. Who, since his death at the hands of the Germans, has also escaped any real recognition or notoriety but had such a dramatic impact at that time. If he had been an officer, it is likely that films would have been made about him to great accreditation. Ken witnessed many escape attempts and indeed was involved in some himself, which again as non-commissioned officers, were not truly recognised.

Again, as a POW, my father would have known the Great Dixie Deans, who with the assistance of Ron Mogg, (also known as John Dominy, an alias for his book that he later wrote) managed the POW camps, which held the NCOs, where Ken was held. He ensured that all the prisoners were treated correctly. He managed the discipline of not only his fellow internes, but also that of their German captors, ensuring that his men were fairly treated and did not suffer the abuse that was experienced in many other camps. He risked his life on many occasions to stand up for his principles.

Ken was involved with the famous “canary”, John Bristow, the operator of the radio receiver produced and carried throughout the war under the noses of the Germans, which kept camp moral so high, enabling them to understand the truth behind the German propaganda that they were so forcefully fed. In the event of necessity, this radio receiver could be converted to a radio transmitter to be used to transmit a distress call should the need arise and call for help.

Ken was lucky to be only involved to some extent with the great marches at the end of the war in what has become known as the Marches to Freedom, when many lives were lost through the sub-zero temperatures, minus 32 degrees, in which they were forced to march with any struggler’s being summarily shot. Then, to his horror, after nearly 4 years of captivity, at Gresse, he witnessed the true cruelty of war when within days of its conclusion and their freedom, a column of POW’s were targeted by rocket firing RAF Typhoons, causing the death of over 60 of them, some of whom had endured nearly 5 years of incarceration at the hands of the Germans and who could now see the end in sight and their return home to freedom and their families. This was not the only friendly fire incident, but the one that would have affected Ken the most.

Can l stress, this is a story not about heroism but duty and patriotism, what everyone considered they should do at that time, to some extent driven by propaganda. It is not particularly heroic but through their determination and conviction, the people of this time demonstrated heroism beyond that which any normal person would endure. This is based on fact, not found in the history books but nevertheless includes at least four events which should be, namely 1st July 1941 and that particular loss of life, which l have covered here, the Sergeant escapers throughout German occupied Europe, the heroism surrounding a typical Londoner called George J W Grimson and the Scot Dixie Deans and the accident, for it was a tragic accident, at Gresse. In comparison with what the POW’s at the hands of the Japanese suffered, we all believe that the captive service men had a comparatively easier life under German control, which cannot be disputed but that is because the stories about what the POW’s suffered under the German‘s has not really been told. This in no way attempts to dismiss the horrors that the POW’s in the Far East suffered, but more attempts to raise the awareness of what happened closer to home. What cannot be denied is the fact that there were many crimes committed against allied POW’s, individual and groups and that one in twenty of every airman that fell into the hands of the German’s, forces and people, never returned home alive. This is a little-known fact that should not be ignored.

The way that the German’s treated their Russian POWs was barbaric, killing and starving them at every opportunity, so close to the main allied POW camps that their atrocities were witnessed by them all, but they were not covered by the Geneva Convention and their soldiers would carry out the same atrocities and worse as they marched through to capture Berlin.

Prior to entering muster as fully qualified Bomber Crew, all RAF personnel received training in what to expect if they were taken as Prisoners of War. Early on this was based on experiences from the First World War, however, as more and more prisoner escapees or evaders returned to Britain, this information became very useful and accurate as to what everyone should expect, in fact returning servicemen were sent on tours of Operational Training Units (OTU’s) to bring the newly qualified servicemen up to expectations.

This did not stop a very few newly captured RAF personnel from deciding for themselves, through shock or shame, that the Germans already knew too much and that the chances of Britain succeeding were so slim that they better help the Germans, in return for enhanced rations. These stories are covered elsewhere, and l will not dwell on this point but suffice to say, it happened.

Equally, upon capture, the standard phase, ‘for you the war is over’ is so far from the truth as very few POWs accepted that they should sit out the war, deciding to either return home or better themselves through education or recreation for when they could return home. Most aircrew considered that it was their duty to continue the war by escaping, not only to return and continue fighting but also to ensure the maximum number of guards were tied up, either ensuring they remained in the Prisoner of War camps or were out there trying to find them. It has been stated that this was the officer’s code of conduct, but in fact more NCOs escaped and returned to Britain than officers, showing that this was widely accepted by all RAF aircrew and other areas of the Armed Forces alike.

That said, there are two parts to the story that we do not know as fact, how it started or where it finished, why he joined up and where he was liberated. I am writing this with the premise that ‘My father would have’ rather than ‘Ken did this or that’, based on the lack of knowledge l have of my father’s actual exploits but this will give a very good insight into what a typical RAF flyer experienced throughout the war years. That said, this account is based on as many facts as l can muster, preferring to use others descriptions of events where l can, to describe what they went through, for which l and many are eternally grateful.

So, the story begins.

Keith Simpson recalls Ken Fenton telling him how he was so impressed when one of his former colleagues at BOCM (British Oil and Cake Mills) in Selby, Ted Cryer, returned to his place of work to show off his uniform, and how smart he looked with his newly acquired wings.

Was this the influence that encouraged Ken to join the RAF or the pictures and news of the returning soldiers, escaping from Dunkirk, the evacuation of which came to a conclusion on 4th June 1940. Ken was destined to form an alliance with some of those who were unable to escape from France or who had been captured during the withdrawal. He was also likely to see many of the soldiers as POWs in the coming years, many of them in his early Prisoner of War camps awaiting repatriation, who suffered terrible wounds during these early battles.

The Battle for France began on the 10th May 1940 when the Germans invaded the Low Countries of France and in less than a month, the British and Allied forces had been evacuated from Dunkirk. It had been costly for the British in terms of soldiers, pilots, aircrew, ground crew and equipment with nearly 500 fighter aircraft lost and over 250 pilots killed. It could have been a lot worse with many, including Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, in charge of the British RAF Fighter Force, arguing that the coming defence of Britain was more important than any goodwill gestures in the defence of Europe, which at this point was probably and realistically, only thought to be a delaying action, as Britain was not prepared to face a full Battle with the well prepared German war machine. The fighting in France cost the RAF a total of 1,029 aircraft and over 1,500 personnel. In terms of loss of life, RAF Bomber Command’s casualties were nothing less than horrific. During the costly Battle of France, in one raid by Blenheim’s on 17th May 1940, eleven out of twelve aircraft from No. 82 Squadron were shot down in daylight raids on German armoured units. The one Blenheim which survived the action crash-landed on return to RAF Watton and was damaged beyond repair. The remnants of the last RAF fighter squadrons in France did not evacuate their bases, preferring to support the evacuation, until 18th June 1940, 14 days after the completion of the evacuation of Dunkirk, having provided cover for the final Allied retreat from France.

Unknown to Ken, Sergeant Victor Charles Salvage, someone who he would become acquainted with and who he would spend his last days of captivity with at Fallingbostal was already fighting in the rear-guard action, covering the much unknown continued retreat from France after Dunkirk, which was still going on for the beleaguered Scottish regiments and others, who were being driven South before the invading German forces in France. These forces were still trying to fight back, whilst also trying to find a way back to England and their story would continue for days and weeks after what is considered the end of the evacuation at Dunkirk.

Victor was aboard a 40 Squadron Blenheim, L8827 BL-?, when it was lost on 6th June 1940 on a raid on St. Valery. Prior to joining up, he was a student before becoming career aircrew with the RAF and I have had the pleasure to meet his widow, the fantastic Ivy Salvage, and help her find out what Victor did and what he went through during the war. Ivy told me that Victor said very little, a familiar story that will be told many times here, but what he did tell her, she found difficult to believe, until one day on Waterloo Station, Victor suddenly saw someone from the past, a fellow POW and his wife, who not only called him ‘The Monk’, a name he had told her, but also confirmed an important story that had been retold. Ivy took the stories in a different light in future but very little more was said. He tragically died in August 1954 in a motor bike accident coming home from work, leaving Ivy and two girls. Victor listed his next of kin on his POW Liberation Questionnaire as being ‘through (father) T C Salvage at 1A Vicarage Road, Eastbourne’. Ivy and Victor were known to each other through the family and got together and married after the war. However, back during the retreat from France, Victor’s aircraft was sent out on 6th June 1940 on a target in St. Valery, the aircraft being airborne at 08.15 Hrs from Wyton, but the aircraft was attacked by six ME109’s, it was shot down out of control. The crew were given the order to bail out and Victor Salvage landed in a cornfield in full view of a large German Head Quarters establishment and was immediately surrounded and captured. The crash site has not been established but Victor stated he was captured near Abbeville, France. Victor’s pilot, S/L Brian Paddon also became a POW, as did their Air Gunner/Wireless Operator Sgt Terence Alexander Foreman POW. Sgt T A Foreman was interned in Camps L1/L3/L6/357, PoW No.64. S/L B Paddon in Camps L1/20A/L1/04C but escaped captivity and was awarded the DSO for his ‘home run’ in August 1942. Sgt V C Salvage in Camps 20A/L1/7B/L3/L6/357, POW No.13076. Foreman stated in his Liberation Questionnaire ‘Unsuccessful attempt at tunnelling, Barth. Worked on staff of “Tally Ho” organisation at Heydekrug.

It is known that the Battle of Britain was not an influence in Kens decision, it had not commenced, the RAF reporting the first day of the Battle of Britain as 10th July 1940, but peer pressure clearly was, together with the view of the many bomber aircraft, sporadic training at this point in the war, from the Yorkshire Bomber Command airfields clearly viable overhead. We know that Peter Mayhew assisted returning Dunkirk veterans and that this had a profound effect on him.

What we also know is that conscription came into place on 26th May 1939 with the passing of the Military Training Act, but this was geared mostly at meeting the needs of the Army, but it did place an obligation on all men reaching the age of 20 to undergo training in either the Royal Navy, Army or Royal Air Force, and then serve 4 ½ years in the reserve. This act was replaced on the outbreak of war by the National Service Act but the age of 20 remained the age of conscription at that time.

Ken first approached the RAF Recruitment Offices in April 1940 at the age of 19, clearly that of a volunteer. We are unsure of the exact date this would have been, but we do his first recorded date was 12th June 1940, just over a month before his 20th birthday, when he stood before the No 5 Aviation Candidates Selection Board (ACSB) at RAF Padgate, near Warrington, Lancashire, telling us he volunteered a few months before he would have been called up through the National Service Act. The likelihood is, therefore, that whilst he clearly volunteered, he did so at a time to try to get some measure of control over the service in which he would eventually serve. At that time, conscripts were usually called up for the army, with only a few being drafted into the Navy and RAF, however due to the need to fill the ranks of the Army as a priority, the process for recruiting RAF personnel was closed at the beginning of the war and only re-opened in April 1940 so Ken would not have been able to volunteer much before the date he did. The time span here does indicate that Ken initially volunteered at the first opportunity in April 1940 so Ken would not have been able to volunteer for the RAF much before the date he did. The time span here does indicate that Ken volunteered for the RAF at the first opportunity in April 1940.

We are not sure of Ken’s motivation for joining the RAF, nor are we clear as to where Ken was liberated some years later, but let’s not let the lack of facts stop the story being told. What is written here are the facts, together with other people’s experiences, people who rubbed shoulders with Ken, through this period of history.

From the early stages of the war the RAF volunteers flowed in thick and fast, mainly believing in social justice and with a profound sense of duty, the majority barely out of their teens, but they would soon look much older. Many men either remembered the atrocities of the trenches or had been told about them first hand and so they would not want to join the army. The RAF was a much more romantic vision, and many volunteers put this down as their first choice, only to discover that they were then transferred directly to the army, this despite the shortages of bomber crew members and the need to rush them through training. The Battle of Britain was destined to start on 10th July and last until 31st October 1940, so the vision of spitfires fighting in the sky’s overhead is unlikely to have been a major factor in Ken’s decision, but it had been announced that the RAF would start to take recruits from the age of 18 to build the aircrew that they needed.

Ken Lister who trained with Ken Fenton as part of 56 Course at 2 SFTS, Brize Norton, said:-

“It all started before the war when the sight of an aircraft was an unusual event. When the sound of a plane was heard, we would all dash outside to see it fly over and pass out of sight. In my case, the dream of being an engine driver, which was every boy’s ambition, was changed into that of becoming a pilot. I was also influenced by the fact that the Central school that l attended encouraged boys to sit the examination for entry to the R.A.F. Apprentice School at Halton. Those who were successful always came back to school to show off their uniforms and tell the rest of us what a marvellous life they enjoyed resulting that many of us looked forward to following in their footsteps. However, when l was old enough to sit the examination my mother put her foot firmly down and said no son of hers would wear a military uniform as long as she was in a position to stop him.”

The two Ken’s were to remain as friends during the war, a picture of Ken Lister was found in Ken Fenton’s POW Wartime Log, sent to him in Stalag Luft 6, Heydekrug.

This shows the emotion following the First World War and the peer pressure, but there was also the fear of conscription and the lack of choice that this would bring.

Peter Mayhew, who also trained with Ken at the Initial training wings and learnt to fly with him in Perth was also at 2 SFTS at the same time as the Ken’s, but his inspiration was different. He spent two nights, Saturday and Sunday 1st and 2nd June 1940 on the platform of Cheltenham Station, handing out tea and biscuits to the returning soldiers, collecting notes to be sent home to let their families know they were home safely. The following day he wrote to the father of a girl he knew who was a retired Group Captain but had gone back to interview recruits at Padgate, Lancashire; ‘as l had not the faintest idea how to join and he told me what to do and exactly what would happen. So, l went to the recruiting office and Volunteered for the RAF air crew as a pilot’. Peter, however, went to Cardington for his interview and medical.

He went on to say ’At the time there was a great shortage of pilots, so l passed without trouble and took the ‘oath of allegiance’ in one of the great airship hangers, 800 feet long, 80 feet high.’ After his interview, he returned home to await notification of when active service would start.

These volunteers did not set out to destroy Germany and they were unaware of the destruction their bombs would eventually cause, but they were driven by patriotism and held authority in a high regard, despite the images of World War One. They believed in what they were told, this was peculiar to both sides of the conflict, and reflected the attitude of the time.

There were various propaganda posters and leaflets that encouraged the young volunteers to join the RAF, promising opportunities, learning a trade and excitement. Noel Monk wrote two booklets, ‘Taking Off’ and ‘With the RAF’. It is of note that the Army version was ‘Eyes Right! The Army of To-Day’ by Captain A. O. Pollard, V.C., M.C., D.C.M. to distance themselves from the Old Army of the First World War.

Following Ken’s initial approach to the recruitment centres and his application to join the RAF, he was called up and instructed to attend No 5 Aviation Candidates Selection Board (5 ACSB), sometimes referred to as Air Crew Selection Board, on Wednesday 12th June 1940 at which time he was told that he was being considered for the vacancy of Aircraft Crew and he was required for attestation. He was told that he would be required for about two to three days at that time but would not be required for immediate service and following attestation, he would be told to return to civilian life pending a recall to service. Upon his arrival at Padgate, using the Railway permit he would have been sent, he undertook two days of selection tests and examinations in maths, geometry, English grammar and composition, etc., as well as medical tests and tests for colour blindness, tunnel vision, night vision, further medical examinations and physical fitness tests etc.

This was all to establish his stamina and aptitude before he came up for interview in front of 5ACSB, when Form F2171 would be completed on 13th June 1940 at the age of 19, 7 days after Dunkirk. Form F2171 graded each candidate on their general intelligence, SMA3 results, general knowledge, maths and English, as well as the candidate’s levels of courage and determination, initiative and responsibility, interests in flying and ability in team and competitive sports.

The Sensory Motor Apparatus or SMA3 was used to work out the potential pilot or aircrew’s dexterity and ability to manipulate a turret, work a trigger and work out his reaction time. It was used to score his ability.

The Aviation Candidates Selection boards were tasked on recruitment, but the assumption was that the bottom 25% were not acceptable, whatever their grades or the grades of the others.

In Britain as opposed to the US, there was an institutional selection process as opposed to one using and basis of Psychology, this was more noticeable in the RAF than any other selection process for the other services. Here, the candidates were questioned whether they played sports, owner a car or rode horses or hunted, many pastimes that were more limited to the richer generation or public-school boy, these questions carried more sway than most. Language and regional accent also counted. The Aviation Candidate Selection Board consisted of a number of high-ranking officers, Top Brass, and a couple of civilians sitting at a table with a single chair in front of the table, on which Ken would have sat, quite daunting. He would have been asked what sports he played, which clubs he belonged to, etc. The civilians were analysing the recruits whilst the Officers decided on the potential of the recruits to be officers. Was this where it was established whether you were fighter or bomber material, Officer or NCO candidates? There were recorded instances of one of the officers pulling out a pistol and pointing it at the recruit to judge what sort of reaction he gave. In 1942 the selection board’s changed tactics to try to select the required number of pilots, navigators and bomb aimers.

Following this interview, Ken was told that he had been accepted for pilot training at that time and promoted to AC2 and given his silver VR lapel badge. Upon being told this, Ken was given the option of starting service straight away as an aircraft hand or being put on a deferred list until he could be put on a pilots training course. Ken chose to defer and avoided many months of ground duties, including peeling potatoes, etc. He was immediately transferred to Reserve on 13th June 1940, in his case No 3 Reception Centre, Reserve and was instructed to return home, continue in his civilian occupation, and await further instructions.

Signing on and taking the first steps towards joining the RAF.

Orders duly arrived and he was instructed to attend the RAF Reception Centre at Babbacombe, near Torquay on 5th July 1940, where he received his initial training at No. 1 Receiving Wing (1RW) whose Headquarters were at the Norcliffe Hotel, Babbacombe, Paignton, Devon. He arrived with a small suitcase and the clothes he was wearing. Here, they were fitted out with their uniforms, which were either too short and too narrow round the waist, or too long and too wide. The jackets fitted where they touched, and the boots seemed to be made of lead. They were also issued with a kit bag, one greatcoat, one groundsheet, and two pairs of everything else, forage or fore and aft caps, socks, vests, pants, shirt, collars, ties, trousers, tunic and rubber soled boots. No one was measured; everything was sized based on the judgement of the issuing stores men. If the trousers were too big, they were issued with a belt, boots too big, then they were told to wear an extra pair of socks.

‘The first stage at a R.A.F. receiving Wing, where newly-arrived cadets are receiving their full complement of kit and equipment before they start training. They have successfully passed the candidates selection board.’

Nothing was assumed, everything was checked.

They were also issued with a knife, fork and spoon, shaving stick, hairbrush, button cleaner and polishing stick. The next few hours and days would be spent making their uniforms look presentable, polishing the buttons and softening and shinning the boots. He was also issued with the standard bed, biscuits (thin mattress in three parts), blankets, pillow and bedside locker, all of which were very basic and hard. He was then directed to a room in one of the hotels on the sea front, which he would share with a number of other recruits. The hotel had been totally emptied of all furniture, curtains and carpets to protect them for after the war. Once he was in his uniform, his civilian clothes were packed in his suitcase and sent home.

They were also issued with their Dog Tags, one red and one green, octagonal in shape and made of a Bakelite-like or pressed fibre material, worn around the neck on a 38″ length of cotton cord, one tag was suspended below the main tag. Letters & numbers apparently punched in by hand, not via a machine. They were told that one was water-proof or resistant to salt water, the green octagonal one and the other, the red round one, fire-proof, giving them all a further point to reflect on as to what was in store for them. The Dog Tags noted the surname and initials, service number and religion together with the letters RAF, any mistakes were not easily rectified so were not reported. It was the intention that the red identity disc would be sent to the squadron or to report the death and the green one left on the body for identification purposes later.

Although he was billeted in a hotel, rather than barrack’s, the hours were strictly enforced by the RAF police patrolling the area and anyone caught outside of the strict curfew of 10.30 PM was subject to arrest and a charge.

Here, Ken completed more forms, undertook further exams as well as receiving a month’s basic training, square bashing and instruction in physical education. They had medical inspections, inoculations, and vaccinations on a mass production basis. Straddling a very long bench, the recruits were told to shuffle forward, being in a perfect position to receive their jabs. The bonus to this was being given 24 hours excused duties to allow the effects to wear off.

Peter Mayhew recalls being told to go to No 1 ITW at the beginning of August. He said:-

‘I caught a train from Cheltenham in the evening and at Bristol met another chap on his way to the same fate. We arrived in Torquay about 7.30-8.00 am and l asked a corporal outside the station where the aerodrome was. He said, “there is no aerodrome anywhere near Torquay and if you have just come to join the RAF you won’t see one for two months or so”. I did not think much of this and nearly caught a train home. However, we went to the Palm Court Hotel for the late breakfast after which, somewhat reluctantly, l went to Babbacombe where we were lodged in the Babbacombe Hotel. A lot of time was wasted being issued with uniform and weird kit and being jabbed for tetanus, typhoid and, doubtless, hysteria. These came with a solemn warning not to drink for 48 hours or so. However, the warning was valid because one or two people who ignored it were seriously ill for some weeks’.

‘On going into a fellow recruits room l saw a photo of a cousin and was informed she was his fiancé – sadly he was killed before they could marry’.

Peter recalls spending ten days at Babbacombe ‘learning the basics of how to salute, how to march, how to stand at ease, how to stand at attention and so forth’.

Typical station routine.

‘Pay parade at a R.A.F. Initial Training Wing, where embryo pilots and air observers are learning. The cadets are paid 2s.6d. per day. These smart-looking young fellows hope before long to earn their wings.’

‘Led by their drum major, Phillip MacLaglan, the R.A.F. cadets have formed their own band at the Initial Training Wing. The white flashes in their caps show that they are under training for air-crew duties.’

Whilst Ken was here, he would have heard about and maybe witnessed but very much on the fringe, the Battle of Britain, which started on 10th July 1940 when a German fighter Squadron first reported a British convoy about to pass through the channel. This German Fighter Squadron supporting a reconnaissance aircraft, was engaged by British fighters, but not before reports were relayed and a larger formation, including bombers, with fighter escort, was sent to intercept the convoy. This bomber formation was engaged by an additional four Squadrons of British fighters, even then the British fighters were outnumbered by 10:1. Additional Squadrons were therefore instructed to get air born and join the battle. Subsequently, no shipping was lost in this encounter.

These shipping strikes continued by the Luftwaffe with a proportionate response from the RAF over the next few days, with German seaplanes picking up downed aircrew in the channel. It was therefore a concern that these seaplanes, whilst clearly displaying a Red Cross and acting to recover downed airmen, were also reporting shipping movements and reducing the Luftwaffe’s loss of aircrew so an instruction was issued for these aircraft to be shot down.

On 16th July 1940, Hitler issued Directive No. 16 with instructions on the preparation of the invasion of Britain, Operation Sea Lion, and gave a final ultimatum to Britain to capitulate. The following days saw an invasion force start to be prepared on the other side of the Channel, but Germany had misjudged the resolve of the British, even though the rest of the world probably considered it only to be a matter of time. Germany first invaded the low countries of France on 10th May 1940, the end of the Phoney War, and their progress across France and indeed Europe suggested little else, with the surrender or France and Europe following very quickly afterwards.

At this time Britain had four twin engine bombers in its arsenal, the Blenheim, Hampden, Wellington and Whitley. The Blenheim had a capacity to carry 1,000 lb of bombs whilst the Whitley could carry 7,000 lbs, but neither were heavily defended with machine guns and they only flew at about 250 mph, which was very slow for the time, their adversarial fighters flying at 350 mph. The four engine heavier bombers, the Stirling, although planned in 1936, came into the front line in February 1941 with a bomb capacity of 14,000 lbs with the Halifax following a month later with a capacity of 13,000 lbs. The Lancaster would not be available for a full year later, in March 1942, but Bomber Command had to make do with what they had, taking the fight to Germany, with the limited resources they had available to them; all respect to the aircrew involved. Whilst the Lancaster is acclaimed as the most successful bomber of the RAF during the Second World War, carrying 22,000 lbs of bombers, ken and his generation did not have a choice and the Lancaster was not available. Losses, therefore, continued to be unsustainable. The phoney war was no indication of their ability. Due to unsustainable losses, night bombing became the normal duty of Bomber Command, but the Blenheim’s were required to continue their daytime operations with horrendous losses.

Meanwhile, back in Britain, it was clear to those at home that they had to fight on alone and at that time the only way to do so and kick back against Germany was through Bomber Command. A production capacity was put in place to provide the bombers and a requirement for recruiting and training pilots and aircrew was realised, but first Britain had to resist the immediate threat of invasion, whilst at the same time hitting Germany hard, not only on the invasion fleet, but also their production facilities and airfields in Germany and occupied Europe.

From the 15th May 1940 and the end of the Phoney War, Britain commenced their bombing offensive against facilities in Germany, a few days after Germany invaded France, but the actual effects of these offensive strikes was minimal. Learning their lessons from the withdrawal from France, night bombing became the preferred method but the accuracy of this was dire, although less costly in aircraft. A few months later a survey was carried out that suggested that only one in three aircraft hit their targets in occupied Europe whilst one in four hit the targets in Germany, in the Ruhr, one in ten, but this was based on the nights with better visibility, those without had much worse results, some, too many, only getting within 5 miles of their target. Even this was achieved only with heavy losses from the RAF, not a good result. Even with the introduction of the Lancaster, their ability to hit their target, was not improved and a study of a raid on Essen in March/April 1942, suggested that only 10% got within 5 miles of their target. Accuracy was left to specialist Squadrons. Even the heavily defended US Air Force suffered unacceptable loses during their daytime operations, and eventually suspended them until they had fighter support all the way to the target and back.

On 1st August 1940, Directive No. 17 was issued instructing the Luftwaffe to now start to bomb the RAF fighter Stations, aircraft factories and radar installations in order to gain the necessary air superiority for the invasion of Britain to succeed.

On 19th August 1940, a spell of bad weather prevented major flying operations and gave the British fighter aircraft a well needed rest during the Battle of Britain. The RAF moved their squadron’s around to give those most involved a badly needed rest. They also arranged for 12 Group fighters to fly south to defend 11 Group’s airfields whilst they were intercepting the Luftwaffe off the British coast.

During his time at Babbacombe, Ken received notice that he was accepted as suitable for Pilot Training and was re-mustered as u/t Pilot and he progressed on to No. 4 ITW (Initial Training Wing) at Paignton, Devon on the 19th August 1940. Being relatively close to his first ITW, the 200 recruits from No. 1 ITW, were marched down the coast to their new home and joined another 100 recruits who were existing serving airmen arriving from various units of the RAF. 100 of the recruits were assigned to No. 3 Squadron and 200 to No. 2 Squadron of No 4 ITW, being inspected by The Viscount Trenchard, Marshal of the Royal Air Force on 30th August 1940.

Torquay’s main contribution to the war effort was by providing hotels for the RAF in which to train aircrew. In addition to the RAF Hospital at the Palace Hotel, Nos. 1 and 4 ITW (Initial Training Wing) were formed at Babbacombe in June 1940. Headquarters were at the Northcliffe Hotel whilst the Sefton, Oswalds, Trecarn, Foxlands and Palermo Hotels were being used for sleeping, etc. Postings were made from Babbacombe to Elementary Flying Training Schools (including overseas in Canada and Southern Rhodesia) where they became pilots, observers, W/T operators and wireless operators/air gunners.

Peter Mayhew recalls that he was posted across to the other side of Torquay to the Hydro Hotel in Paignton.

From the first intake of 579 recruits in July 1940, a month before Ken arrived, almost a further 27,000 airmen were trained there before the Wing left Babbacombe. No 3 ITW also came to Torquay in June, its headquarters were at St. James’ Hotel (now Harbour Point). Further hotels in Beacon Terrace were requisitioned, together with Park Hall Hotel, the Regina Hotel and the Dorchester and Devonshire Hotels were requisitioned later in February 1943. St. Vincent’s Hotel (now flats) was taken over for use by the WAAF.

A fourth ITW was No 5, which also moved to Torquay in June 1940. Headquarters were in Castle Chambers, later moving to the Hotel Metropole, now the Cavendish. A full list of hotels used is not known but they included the Majestic, Seaton and Stanbury Hotels which were damaged on 30 May 1943 and had to be evacuated.

After the war, Ken maintained an affection for this area of England and many family holidays, and indeed his honeymoon were spent here, perhaps my father was quietly re-visiting the various places he had seen during his time in training, but this was not apparent to me.

The following is an extract from Winston Churchill’s speech to the House of Commons, made on 20th August 1940, which sets the scene for the patriotic attitude in Britain at the time.

“The gratitude of every home in our Island, in our Empire, and indeed throughout the world, except in the abodes of the guilty, goes out to the British airmen who, undaunted by odds, unwearied in their constant challenge and mortal danger, are turning the tide of the World War by their prowess and by their devotion. Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.”

“All hearts go out to the fighter pilots, whose brilliant actions we see with our own eyes day after day; but we must never forget that all the time, night after night, month after month, our bomber squadrons travel far into Germany, find their targets in the darkness by the highest navigational skill, aim their attacks, often under the heaviest fire, often with serious loss, with deliberate careful discrimination, and inflict shattering blows upon the whole of the technical and war-making structure of the Nazi power.”

“On no part of the Royal Air Force does the weight of the war fall more heavily than on the daylight bombers, who will play an invaluable part in the case of invasion and whose unflinching zeal it has been necessary in the meanwhile on numerous occasions to restrain.”

With Germany’s intention to invade Britain, the Luftwaffe continued to attack military targets and ports around the South Coast and further inland. The first German attack on London actually occurred by accident when on the night of 24th August 1940, Luftwaffe bombers aiming for oil installations at Thames Haven, on the outskirts of London, in the darkness flew over their target and instead, in contravention of their orders, dropped their bombs on the centre of London, destroying several homes and killing civilians. Amid the public outrage that followed, Prime Minister Winston Churchill, believing it was a deliberate attack, ordered Berlin to be bombed the next evening.

The following evening as instructed, and as a prelude as to what was to come, about 40 British bombers managed to reach Berlin and inflicted minimal property damage. The Germans were, however, utterly stunned by the British attack on their capital, being the first-time bombs had ever fallen on Berlin, having been repeatedly assured by the Luftwaffe Chief, Hermann Göring, that it could never happen. A second British bombing raid on the night of 28th/29th August, resulted in German civilians being killed on the ground and two nights later, a third attack occurred. Bomber Command would continue these attacks against all odds and continued to attack Germany and the occupied countries, which slowly forced the Germans into a defensive roll, with fighter production increasing and bomber production reducing as the war continued.

Whilst the British aircraft industry was under repeated attack, they were able to maintain a constant supply or replacement aircraft in support of the Battle of Britain and the bomber offensive against the invasion barges on the French Coast but the system was struggling to replace the pilots and aircrew lost, either killed or injured and many trainee pilots and aircrew were rushed through and sent to both Fighter and Bomber Command with reduced hours of pilot training and very few hours on their intended aircraft, but this was to become the accepted standard for the foreseeable future.

On 4th September 1940, in response to the British attacks on Berlin, Hitler made his speech to the German people promising a sustained attack by German bombers on Britain and instructed attacks on London and other industrial Cities in Great Britain and on 7th September 1940, this would commence with a large raid against London, both day and night. This was a big mistake by Germany as it gave the British fighter squadrons and their stations a well needed rest, without which they may have well run out of pilots, if not aircraft. The raids on London, however, increased but so did the resolve of the British population.

On 15th September, now known as Battle of Britain Day, the Germans sent their biggest Bomber and Fighter force yet against London as a last push to overwhelm the last few British defenders and break the countries morale. This possibility was supported by over optimistic results of British losses reported by returning Luftwaffe pilots but was proved to be incorrect with a large number of Luftwaffe aircraft being lost that day.

On 17th September 1940, with the weather changing and the obvious resolve of the British Fighter Command and their ability to continue to defend the British Isles, Germany cancelled Operation Sea Lion indefinitely and resolved to bomb Britain into submission. Daylight raids continued until 30th September 1940 but the results on that day proved too costly to the Luftwaffe, and they therefore ceased large scale daytime bombing raids on Britain. The night-time raids would continue with significant losses.

Winston Churchill in his famous speech would later refer to the Fighter Pilots as ‘The few’ but in the years to come, fighting against staggering odds, the men and women of Bomber Command were to make their own sacrifice as ‘The many’.

At 4 ITW, for 6 weeks, Ken together with his fellow cadets took part in basic training with drill, more square bashing, PE, classroom work, cross country runs and long-distance route marches with full kit, etc. in preparation for the next stage of training. It was a ground school, for hopeful pilots, a course of 12 – 14 weeks in theory of flight, engines, meteorology, navigation, signals, including Morse, radio and the aldis lamp which ended with a passing out examinations plus various psychological and aptitude tests.

‘Cadets at R.A.F. Initial Training Wing are told of many stirring experiences by famous operational pilots, observers and air gunners (above) Flight Lieut. J. Nicholson, V.C. is relating an amusing experience to trainees.’

Peter Mayhew’s memories showed no real excitement:

‘Still no aeroplanes, but marching up and down the promenade learning Morse code, airmanship, how to conduct yourself in the air, i.e. giving way to anyone on the right and doing PT’.

The station at 4 ITW was on high alert at this time in readiness for a German invasion from France and anti-parachute measures were in place to protect the area. Plans were also put in place with a view to destroying any fuel or ammunition that would have been left during a withdrawal. Vehicles were to be demobilised by draining out any fuel, letting down the tyres and removing steering wheels. Each recruit was required to get involved in guard duty, issued with rifles which no one thought were loaded.

Peter Mayhew recalls:

‘One of the other things at this fiendish place was guard duty at the front porch of the hotel. They gave us a rifle which most of us had not the faintest idea how to use. I think they had the sense not to give us any ammunition. There was a long-distance route march with full kit, four or five of us slipped out after about a quarter of a mile into a pub and waited for them to come back when we rejoined for the last quarter of a mile. Doubtless marching somewhat unsteadily – l was 18 years old,’ with ‘scrumpy at 2 1/2d a pint. This nonsense came to an end about the end of September 1940 (likely to have been more like October as there were no courses at Perth at this time unless they were given some leave) when our Battle of Britain ended.’

‘The lunch-hour rule at an Initial Training Wing is “First come, first served.” The eager faces of the cadets indicate that their appetites are good. Practically every cadet carries his respirator.’

‘An Officer lecturing on aircraft identification to a class. Care is taken with this, for as the instructor says, quick and accurate recognition may decide “Between a dead Boche and catching a packet.”’

THEY WILL FLY AGAINST THE ENEMY (CH 2107) Original wartime caption: Captain Balfour, accompanied by the Air Commodore in charge of initial training of aircrews, watched a march past by cadets at the I.T.W. Copyright: © IWM. Original Source: http://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205443286

Air cadets march past for inspection.

All personnel were trained in defence, fire drill, dinghy use and ditching procedure in Torquay swimming baths and harbour. Everyone was told that by the end of the course they would be able to swim and be capable of life saving, so plenty out of hours training at the local baths took place. Dinghy practice took place in the harbour, regardless of weather, dressed in Sidcot flying suits, flying boots, helmet, goggles, gloves and a Mae West life jacket. An inflated nine-man survival raft would be thrown in and turned upside down. The recruits were then instructed to jump in (high tide). Anyone who hesitated was “assisted” by the instructing flight sergeant, and then they were told how to turn it the right way up.

On other occasions, one cadet was instructed to act as if he was unconscious, and he was instructed to float around in his Mae West. A cadet would then climb into the dinghy to pull and another remained outside to push the unconscious man up into the dinghy. They were instructed in the use of all the equipment in the dinghy, flares, paddles, drogue, etc. The R.A.F nine-man survival dinghy was an efficient piece of equipment. When it was inflated by the compressed air bottle, not only were the two big rubber rings inflated but the floor, and top also, leaving only the doors to be inflated by mouth. They were told that with the doors closed even in freezing temperatures, body heat would warm the interior. This proved not to be the case for so many downed crews in the North Sea, but little did Ken know at the time, how important this training would be for the survival of him and his crew to be.

They also learnt the art of clay pigeon shooting and deflection shooting, anticipating a targets flight, together with armaments. Stripping down machine guns in the dark and naming all the parts. Ken maintained this interest in guns for a long time after the war, when he became a keen shot.

Ken is located third from left, back row, wearing a scrum cap.

Unknown to Ken, whilst he was training, on 3rd October 1940, Sgt. Edward (Ted) Francis Cryer, (Service Number 754166, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve) died aged 20, whilst flying a Whitley IV, K9031, with 19 OTU from Kinloss on a night dual training flight. It is not known what happened to the aircraft but in bad weather, at 22.30 hours, distress flares were seen from the direction of Findhorn Bay, off the Moray Coast. The bodies of Sergeant Edward Francis Cryer and Sergeant Elton Arthur Dancer were recovered and taken away for burial, but Sergeant John Anthony Smith’s body was never recovered. The Whitley was later found but all attempts to lift the bomber from the seabed were thwarted due to silting and the prevailing inclement weather. Ted Cryer was the Son of Albert and Annie Cryer from Selby; his body was returned home and he is buried with other service personnel in Selby cemetery. Sgt. Dancer’s body was returned home to Ayr Cemetery, Ayrshire whilst Sgt. Smith, from Droitwich, is remembered at Runnymede, panel 19. Ted was also born in 1920, same as Ken, on 11th April and also attended Read School, Drax, leaving on 3rd March 1938.

No 8 Course Pilots of 19 OTU, of 22nd September 1940. Ted Cryer is third from the right, back row. Others listed are back row Sgts D Angell, D Bellingham, L Blackwell, G Baxter, E Dancer, E Pocock, G MacDonald and front row P/O’s H Hawley, Phillips, H Skyrme, B Kerwin, A Ogilvie and J Louden.

Image of Edward Cryer taken from the Yorkshire Air Museum

Armstrong Whitworth Whitley

‘Above are three Leading Aircraftmen now ready to proceed to their Elementary Flying Training School. They are devoting a few spare hours to improving their knowledge of German and Italian aircraft.’

‘A typical and fine example of Britain’s war youth: Cadets of the R.A.F. at an Initial Training Wing. Parading in flying kit for the first time before going on to their Elementary Flying Training School. (Photograph by Cecil Beaton)’

This picture is thought to have been taken in 1940 at either 4 ITW (most likely), 11 EFTS or 2 SFTS, showing Ken Fenton in his Sidcot suit, flying helmet and radio connections.

On the 4th October 1940, Ken advance to Leading Aircraftsman (LAC) and already re-mustered as a pilot U/T (under training) was posted with 112 other recruits to various EFTS’s. For Ken this meant a posting to 51 GP Pool (Group Pool), based at Yeadon, now Leeds/Bradford Airport. This was the administration Centre for 51 Group Pool, a paper posting, so it usually meant that the Pilot U/T were sent on a pilot selection course of about five weeks to a small airfield, attached to one of the manufacturers.

51 Group Pool was formed in February 1939 as part of the expanding training effort of the RAF, 51 Group of Flying Training Command was already responsible for a number of Elementary Flying Training Schools and Air Navigation Schools. This Group Pool also performed some of the initial flying training, borrowing Tiger Moths from EFTS’s attached to various aircraft production units.

As Ken was posted to 51 Group Pool, this actually meant for him a posting to 11 EFTS (Elementary Flying Training School) at Perth, (Scone) Scotland. 11 EFTS was formed in January 1936 with No. 7 AONS (Air Observer Navigation School) following in January 1939, both schools being operated by Airwork Limited, who had moved from Heston Airport in Middlesex in 1935 to Gatwick as their base.

The school was therefore operated on a civil operations basis under contract to the Air Ministry until 1st January 1940 when all flying instructors and pilots were mobilised. No 7 AONS however closed down on 31st May 1940. They had recreation facilities in the form of 2 tennis courts, 2 squash courts and playing fields, including rugby, football and cricket. They had reserve landing grounds at Whitefield and an emergency landing ground at Scone Park.

Map showing the location of Perth Airfield, 3 ½ miles Northeast of Perth, identified by the River Tay 4 miles to the South, together with the nearby airfield and emergency landing ground at Whitefield and auxiliary airfields at Errol and Findo Gask. Tealing was to the Northeast of Errol.

Ken boarded a train bound for Scotland and was told to report to No 11 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS), which he did on 5th October 1940, along with 45 other pupils and immediately joined No 32 Ab Initio course (Meaning starter course, training from the beginning).

Ken, together with about a dozen from the course at Paignton, were collected from the station and taken by bus to their digs, something that had once been a large private house on the outskirts of Perth, called ‘The Durn’. It was a far cry from the Spartan accommodation at ITW. Here their beds were made, and they were looked after by a caretaker. At the EFTS, the pre-war rules of a civil establishment made for a welcome change from the rules and discipline handed out at ITW.

Peter Mayhew recalls the journey:

‘We caught a train for Perth. Some of the journey was spent chucking, out the window, a fair bit of the kit with which we had been issued. Such a thing called a housewife, a frightful little rolled up thing containing needles, reels of cotton and such like which we had not the faintest idea how to use and no intention of learning. Also, a knife, fork and spoon and a dreadful tin contraption you were supposed to eat out of. After considerable discussion we deigned to keep our gas masks despite their clumsiness. And so we arrived in Perth the following morning and were taken to quite a nice house in the town which had been commandeered and then five miles out to the old airfield at Scone where at last we saw some aeroplanes – Tiger Moths.’

Stephen P L Johnson, on the same course as Ken, said in his book describing his training:-

‘In charge at the ‘Durn’, and responsible for seeing that we got into the bus each morning to go to Scone Aerodrome, was the dirtiest, scruffiest, idlest Flight Sergeant any Airman ever had the good fortune to meet. Never once during our stay did he polish his own boots or buttons and he didn’t care in the least whether we did or not. Scone Aerodrome had been a peace-time flying school. In order to convert it to a war-time RAF aerodrome the instructors were issued with uniforms, but little appeared to have been done to alter their habits. We went there to learn to fly and if it was humanly possible to teach us to do so they did: but they never minded whether we arrived clean and tidy or not. Mark you we were all extremely keen. The preliminary training, when we never saw an aeroplane and sometimes doubted whether we ever should, had been somewhat frustrating. To us the few disintegrating and ancient Tiger Moths with which Scone was equipped were a wonderful sight. The one terrible fear which we all had was that we should be unable to make the things perform their evolutions sufficiently well to satisfy our instructors.’

Enemy photograph of Perth (Scone) airfield taken in 1939 by the Luftwaffe. Camouflage has been attempted with fake hedge lines, but no one was fooled. Second photograph was taken in 1947 and shows a number of Tiger Moths still on the airfield.

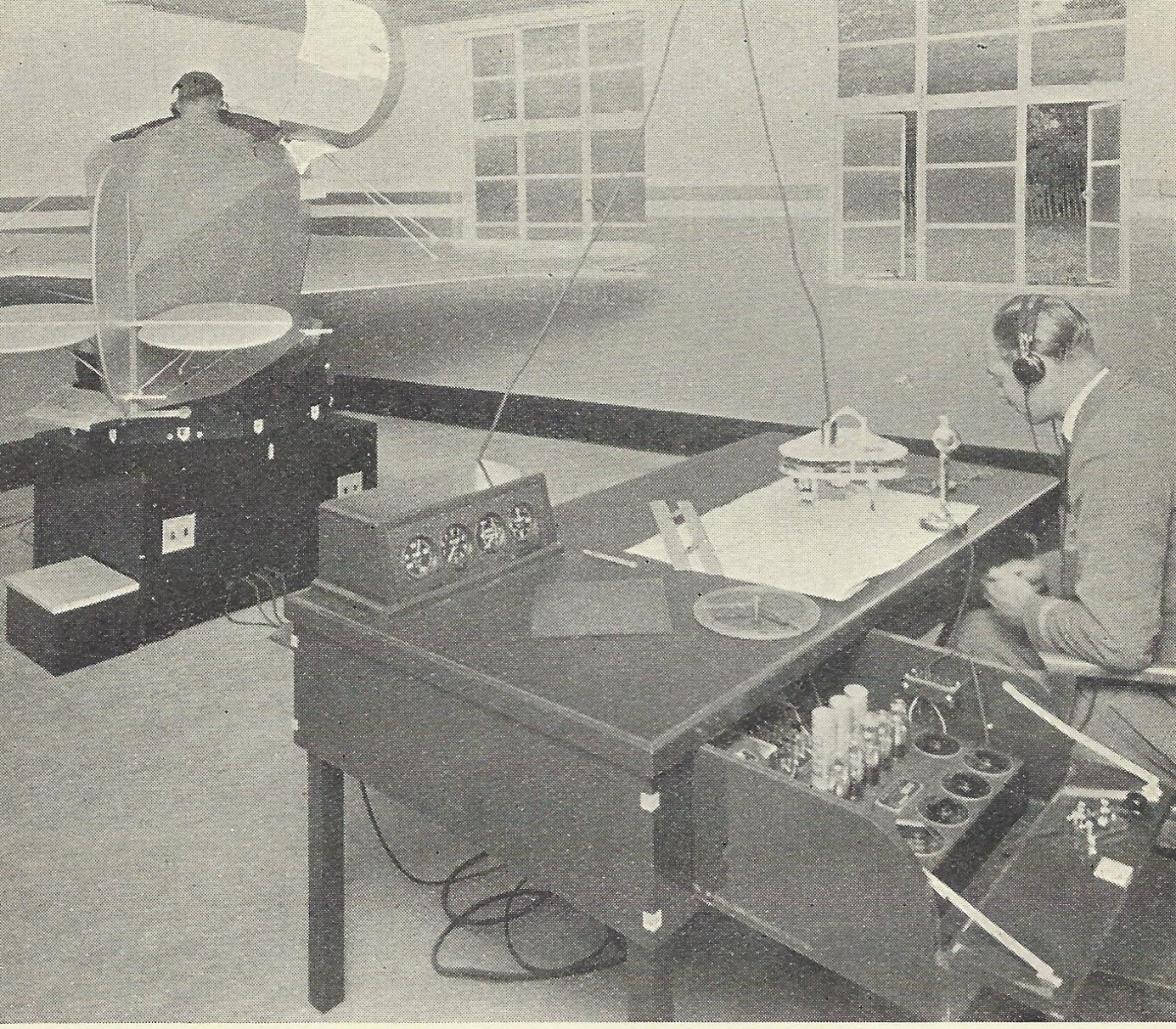

Here, Ken was first introduced to the ‘Link’ trainer prior to his introduction to the Tiger Moth to begin his basic pilot flying training.

Described in The Courier and Advertiser, Monday, June 6th 1938, headed ‘Flyers will learn Bombing indoors, RAF Buys Perth residence.’ It Said ‘One of the most picturesquely-situated houses in Perth – The Durn, Isla Road – has been sold to the R.A.F. Volunteer Reserve.’

‘The house, which belonged to Mr A. E . Pullar, stands on the banks of the River Tay, opposite the North Inch.’

‘It is to be used as an instructional and recreation centre, and one of the latest devices for training is to be incorporated in two of the rooms. This consists of a cockpit, complete with all controls, in which the pilots learns, among other things bombing.’

‘Synchronised with the controls is a projector that casts the picture of a moving landscape, showing churches, houses, and factories, etc. Should the pilot deviate from the course that has been set him this deviation is at once indicated.’

‘ “Hits”, by bombs on this landscape are also calculated, the effect being that the potential pilot receives “flying training” without leaving the ground. Actual flying experience is carried out at Newlands Aerodrome during daytime.’

‘Wing Commander Hall, town commandant told a “Courier and Advertise” reporter that the Durn was to be used as town headquarters.’

‘ “We have an establishment of 50 trainees” he said. “I hope that in the very near future the establishment will be increased to at least 100”.‘

‘The building will also incorporate mess rooms and rooms for recreation, while tennis courts are also to be constructed.’

The ‘Link’ trainer was a dummy aircraft with a cockpit full of all the usual instruments expected to be found in an aircraft that was fixed at one point on an axis and was free to pivot freely around this point in response to the usual movement of the controls. It would tilt sideways, as well as fore and aft, to mimic an aircraft in flight and was placed in a circular room with the walls and floor painted to represent sky and land, giving the trainee pilot the feeling of climbing, diving, banking, etc. A hood was fitted to give the pilot blind flying experience.

Photo showing a demonstration with the “New” Link trainer in the South of England.

RAF pilots get ‘air conscious’. The new link trainer demonstrated.

One of the most important lessons which a new pilot entering the RAF has to undergo is taken in the new form of the ingenious “Link” trainer. The trainer is a dummy cockpit with all the usual instruments. It is free to pivot round its axis and can be tilted fore and aft. An innovation is that it is placed in a circular room with the walls painted to give the impression of sky and land, thus the pupil can go through all the movements of climbing, diving, banking, etc. For “blind” flying a hood is used to cover the pilot. Photo shows a demonstration of the new “Link” trainer in the South of England.

The trainee pilot would sit in the plane and with the hood closed would be totally dependent on his instruments and radio, all simulated by a technician at a control desk. Radio messages and Morse would be relayed to the pilot via a multicore control cable. The Link could also replicate various weather conditions as well as instrument failures, etc. A motor underneath the base pumped air and created vacuums, in various bellows, to give the feeling of rough weather and dive and climb. The Link was also connected to a moving platform on the operator’s desk which traced his course over a map to show the course he would have taken if he was aloft in an aeroplane.

Maintenance and operation of the link Trainer.

Similarly, prospective Air Gunners were put through their paces. The picture shows RAF air gunners in training at an air gunners’ school in England, showing a trainee familiarising himself with the Air Gunners turret on the ground. To give a realistic effect a tail-plane is mounted behind the turret to show the importance of not shooting holes in this too.

Soon after initial instruction on the Link’ trainer Ken progressed to the Tiger Moth. In Ken’s case this would have been the DH 82 Tiger Moth, a two-seater biplane powered by a single De Havilland Gypsy Major 4-cylinder 130 Horsepower engine, the Tiger Moth could achieve speeds of up to 144 mph with a range of 300 miles and an acceptable altitude of 14,000 feet, which first came into service in 1931 as a two-seater trainer. By 1940, 11 EFTS were operating up to 90 Tiger Moth trainers. The DH 82 Tiger Moth, with its open cockpit, would have been a true test of endurance for the trainee pilots during the bitterly cold winter months in Perth, Scotland, where Ken was to learn to fly.

Post Card showing the DH 82 Tiger Moth Trainer, notes on the reverse state ‘Flown at Perth E.F.T.S. 28 Hours Dual, 19 Solo.’

In the early stages of the war there was no need to cut training time and courses to fill front line squadrons but within the space of a few months, this was to change, especially with the fall of France in May 1940 when the RAF suffered its first significant number of pilot casualties, after which, the need for pilots became critical. As there were plenty of volunteers for pilots the RAF only wanted the best, those who could be trained quickly and easily, so the trainee pilots were receiving good quality instruction but were expected to fly solo on a Tiger Moth within only a few hours, typically 10, or at a push 12, to qualify for further pilot training, but nothing was rushed or skimped as plenty of aspiring spitfire pilots were being trained as well. Here at 11 EFTS, the ‘want to be pilots’ received between 30 and 40 hours flying training, 7 to 9 hours flying training per week. At 11 EFTS at the end of 1940, the hopeful pilots had a 33% chance of success and being posted on to further pilot training.

Stephen Johnson went on to say:

‘In fact, this (10 to 12 hours to solo) was a very fair guide to a man’s ability as a pilot. Few people who take longer than that make good and safe pilots however much tuition they receive. We knew that between a quarter and a third of our number would fail to go solo in the specified time and so be posted to other duties. We all thought that we would be one of these disgraced and unfortunate creatures. Goodness knows why we were all so keen, but we were, so discipline was comparatively unnecessary at this stage of our careers.’

Little did Stephen Johnson know the true failure rate at that time, but the Air Ministry obtained a lot of observers and wireless operators/air gunners and later navigators, bomb aimers and gunners from those who were not selected, a way that they could continue to fly, but many did volunteer for these other roles direct.

Peter Mayhew recalled:

‘We spent alternate days flying and lectures and duly went solo after about five and a half hours – l think. This was the greatest day of one’s life; no one sitting in the front cockpit pestering you and alone in the air; wonderful sense of freedom. Before going solo we had to have a test with the chief flying instructor. I failed to arrive on the aerodrome with him, either being about to touch down in the field before the aerodrome or the one after it. We had at all times to make a glide approach and landing from 1,000 feet. After this fracas my own instructor took me up for a circuit and bump. After which he got out and said, “Off you go and don’t kill yourself or l lose my job”.’

Johnson continued:

‘Everybody has a tremendous respect for the man who teaches him to fly an aeroplane. You have a lasting sense of gratitude and admiration for your first Flying Instructor. It is unlikely that you will forget entirely your first girlfriend but you don’t remember her with anything like the same affection and respect as you do the man who says, ‘Well off you go,’ on your first solo flight.’

‘I expect Sergeant Winning was really quite an ordinary little man but to me he was simply wonderful because he could handle a Tiger Moth with such unconcerned skill. On my first flight with him l was scared to death and thought, ‘God, l shall never be able to do this by myself.’ But gradually l became used to it all and even became accustomed to stalling and spinning, which we had to do before we went solo. We were grounded for four days from October 18th to 22nd by bad weather and l was terrified lest l should have forgotten all l had learnt: but luckily l hadn’t and on October 24th l was given my solo test by another instructor. I didn’t think that l was nearly good enough but after doing a circuit with him he climbed out and said, ‘Well off you go and do one circuit.’’

‘There l was without a familiar figure in the front cockpit. The green of the aerodrome stretched away towards the distant hills. After the cockpit checks, l eased the throttle gradually open and went bumping away across the grass. Soon there were no more bumps and l was climbing away at the correct speed with only the familiar sound of the Gypsy engine and the buffeting of the slip-stream on my helmet for company. Then l had a feeling that there was something missing. For a moment, l couldn’t place it till suddenly l realised that it was the fact that l wasn’t feeling at all frightened. I had always imagined that l should be scared absolutely to death on my first solo. I was quite amused to find that l wasn’t. I managed quite a reasonable landing and was as proud of myself as is everyone when he or she achieves a first solo flight.’

‘Naturally this called for a terrific celebration that evening and we repaired as usual to the Salutation (Hotel) where there was plenty of alcohol and some extremely attractive girls’.

‘I don’t think that l have ever in my life enjoyed a month more than the one l spent in Perth. We flew about over the wonderful countryside on clear October days. The hoar-frost glistened in the shade and the sun shone on golden bracken and stubble with the mountains in the distance. The Tay twisted its way through woods and fields. It was all something that l shall never forget.’

‘Even flying one of those ancient aircraft, which were designed before people fully realised why an aircraft stayed aloft, one experienced an elementary thrill which is denied to the pilot of the present day. He sits in an enclosed heated and pressurised cabin. His speed may be many hundreds of miles an hour, but it gives him no thrill. Our speed was only eighty miles an hour, but we were fully aware of every single one of those mph as the air rushed and whistled past our faces. If we glanced up at the ancient wings and the rusty bolts where they were attached to the fuselage, we saw that they moved up and down in an alarming way as the wind buffeted them. It is quite remarkable that these very, very old aeroplanes are still used today to teach people to fly. One might just as well expect to see a pterodactyl flying around.’

‘We didn’t have time to do many aerobatics for l only did twenty hours solo the whole time l was at Perth. I did get as far as looping the loop and felt very brave about it. The first one l did by myself l thought was rather good. I was just coming nicely out of it feeling somewhat relieved to be the right way up again when the aircraft gave the most horrible shudder. I glanced back anxiously around to see whether any essential piece had fallen off but all seemed to be well. Eventually l realised that my loop had been altogether too accurate and that l had flown through my own slipstream.’

‘We were very much spoilt in Perth. The carefree attitude and friendship between instructors and pupils was too good to last’

At this point, it was also decided that Ken was more suited to bombers, rather than fighters.

A bomber crew at the time was described in an Air Ministry publication entitled Bomber Command, which was issued by the Ministry of Aviation in 1941.

“The men of Bomber Command are appointed to fulfil a special mission. Their life is not that of other men – not that even of those in the other branches of the service. It’s very physical conditions are different. For them nowadays much of the night is day, much of the day a time for sleep and repose. Discipline is constant yet flexible…Triumph and disaster are met and vanquished together.”

“The captain and, where appropriate, its second pilot do the actual flying, the observer navigates and drops the bombs; the wireless operator helps the navigator and the air gunners do the fighting. The same spirit and practice of co-ordination is required of a bomber crew as of a crew of a racing eight or the members of a football eleven…”

This explains the frequent questions about sporting preferences and abilities asked at interview.

It goes on:-

“The bomber pilot differs in training and environment from his colleague flying a Spitfire or Hurricane. A pilot of the Royal Air Force is subjected at an early stage to a process of selection by which it is determined whether he is better fitted to fly a fighter or a bomber. Both will have to fly aircraft; both will wear pilot’s wings; but here their ways diverge. The fighter pilot is in action for an hour and a half to two hours at the most, often far less. He is usually led into the fight by his squadron leader.”

“Very different, but equally important, qualities are required of a bomber pilot. He must be capable of considerable physical and mental endurance, for it may be to fly for the most part of the time over hostile territory or across the unfriendly sea. During much of the flight he may find his aircraft the object of attack by enemy assailants can break off and renew assault at any moment. Surprise, that weapon which more than any other wins a fight, is theirs to wield at will. The bomber pilot must fly doggedly on, defending himself with the aid of darkness and cloud outside and with the skill of his crew and their machine guns inside. The bomber pilot must not forget that he is one of a team and that the team is not flying separated from him in another Hurricane or Spitfire, but the same aircraft, crouched over the navigator’s table or hunched up in the gun turrets. He must be imaginative, yet not dismayed by his own imagination, brave yet cautious, cool yet daring.”

Peter Mayhew described the training which they underwent:-

‘There was one chap on the same course who took a Tiger Moth up to 6-7,000 feet and put it in a spin. Unfortunately, it went into a flat spin, a hopeless and uncontrollable situation. He tried to bail out two or three times but each time was knocked back into his seat so gave up and sat and waited. A lot of us were watching this performance and the CFI set off in his car in the general direction of where it was going to crash. When he got there he found the pilot cursing because he had scratched his wrist while trying to bail out and had blood on his shirt cuff, otherwise he was completely unhurt. The aircraft had had no forward speed at all and came down like an autumn leaf. The undercarriage and wing-tip absorbing the shock of the impact – not much damage.’

‘We had to do a solo cross country. This involved flying all the way from Perth to Montrose – 35 miles – where we had to land and get our flight log stamped to prove we had achieved this fantastic journey – one way, and landed at the right place. Part of the training was instrument flying when a hood was pulled over the rear cockpit and the instructor took off and climbed away and then handed over the controls, telling you what height and course to fly. When to turn onto which magnetic course and when to descend, etc.’

‘We had spent two months at Torquay having the initiative and individuality knocked out of us or an attempt to do so. Now and for the rest of our flying training they tried to put both back in again.’

Whilst Ken was at Perth, visits were made by Air Chief Marshal Sir E R Ludlow Hewitt KCB, CMG, DSO and MC on 2nd November and Air Vice Marshal L A Pattinson CB, DSO, MC and DFC on 5th November 1940.

At the end of this course, Ken was recommended for further pilot training, and on 12th November 1940, Ken and 8 other pupils were ‘posted away’ to Brize Norton to commence their bomber training with 2 SFTS, arriving the next day on 13th November 1940. Six others each were posted to both Montrose, 8 SFTS for fighter training and Wilmslow where No 2 PDC (Personnel Despatch Centre) was due to form in November 1940 with a view to sending pilots over to Canada or America to an overseas training unit but this did not happen, so it is assumed that these six were sent to another SFTS for further training in England.

At that time, the UK was not considered as a suitable location for training pilots, due to the possibility of enemy attack, the need to separate operational and training aircraft and the unpredictable climate, so a plan was put forward to train pilots as part of the Empire Air training Scheme in Canada, Australia and South Africa.

The aim was to train some 50,000 aircrew each year; 22,000 aircrew from Great Britain, 13,000 from Canada, 11,000 from Australia and 3,300 from New Zealand. Under the agreement, air crews received elementary training in various Commonwealth countries before travelling to Canada, South Africa or later America for advanced courses. This involved the dangers of crossing the sea, the Atlantic, for instance, by boat.

On 29 April 1940, the first Canadian training course officially commenced, with 221 recruits, at No. 1 Initial Training School RCAF, All of these graduates, however, were retained in Canada, as instructors, staff pilots or in similar flying assignments.

This was not an option for Ken as it was still in its infancy.

Therefore Ken arrived at 2 SFTS, (Service Flying Training School) Brize Norton, Oxfordshire together with 8 other members of 11 EFTS, on 13th November 1940, just 5 months after his enlistment into the RAF.

Peter Mayhew recalled the journey:

‘We boarded a train southbound, probably about a dozen of us, ending up at Brize Norton, Oxfordshire, where we joined up with others from various EFTS to make a course of 50. Some of those from Perth had gone on to further single engine flying. We were on twins – Airspeed Oxfords.’ Peter was a big guy, over 6 ft. and wanted to be a fighter pilot but was probably considered too large.

The following morning, on 14th November 1040, Ken was issued with a pass, allowing him to leave and re-enter the base at 2 SFTS, but only whilst wearing his uniform and not if required for flying or any other duties. The pass was for permission to be absent from the camp between midnight and 22.30 hours, to allow the pupils under instruction to pass around the various training facilities and satellite aerodromes. The document was signed by then Squadron Leader A Adderley.

Copy of pass issued, 14th November 1940 at 2 SFTS.

Together with this pass, a ‘lucky’ symbol was also found, referring to the Apostleship of Prayer in League with the Sacred Heart, marked Veritas Dublin. No connection has been made with this so far.

Map showing the position of Brize Norton airfield, together with its associated affiliated and emergency landing strips.